Why broad-based import tariffs can hurt exports and manufacturing jobs

Across-the-board tariff hikes can inhibit long-term competitiveness because manufacturers rely on imported inputs and contribute disproportionately to overall exports and manufacturing job growth

A new “Washington Consensus” has emerged where higher tariffs feature prominently in U.S. international economic policy. A key objective of the tariff increases is to protect and promote U.S. manufacturing employment. However, the balance of the evidence to date points to few benefits and net costs to U.S. manufacturing activity. A central reason is that U.S. production is integrated into global supply chains and it is challenging to reorient long-established supply links. An examination of newly released public-use statistics reveals the high concentration of trade and jobs at firms that both export and import goods (exporter-importer firms) and thus tariffs on imports can end up hurting export performance and associated employment. Future U.S. trade policy actions should narrowly target stated domestic goals to minimize unintended hits to American competitiveness.

Broad-based tariffs hurt U.S. manufacturing activity as production remains integrated in global supply chains

U.S. tariff policy has shifted markedly: a spate of tariff rate hikes across a wide range of goods were levied beginning in 2018 and continued through 2019, with additional increases announced in 2024. These tariffs are likely to remain high in the near future. Targeted tariffs are important tools to counter unfair trade practices and address national security concerns, however, broad-based tariffs are unambiguously damaging to the economy.1

Contrary to broadcasted objectives of boosting U.S. manufacturing activity, evidence shows that the dramatic rise in U.S. import tariffs between 2018 and 2019 lowered exports and employment in the U.S. manufacturing sector.2 While tariffs on foreign goods provide protection to import-competing industries, they can have a net negative impact on output and employment because U.S. manufacturers rely on foreign inputs in their goods production processes. In fact, half of all U.S. imports are industrial supplies and capital goods that are used as intermediate inputs by manufacturers.3 Tariffs are taxes that make these inputs more expensive; and in the absence of suitable alternatives and inability to pass on higher costs to consumers, especially in the short-term, higher tariffs place downward pressure on output and employment (all else equal). The Federal Reserve’s October 2019 Beige Book, for example, documents that “[b]oth retailers and manufacturers noted rising input costs, often for items subject to new tariffs, but retailers had relatively more success passing through these cost increases to their customers.”

Since the ratcheting of U.S. import tariffs in 2018, several large shocks—notably the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—have roiled U.S. firms’ global supply chains. Nonetheless, overall U.S. imports have remained robust. Although early evidence indicates reallocation among source countries, U.S. firms’ reliance on foreign goods, including inputs, remains strong despite facing higher import prices. An important takeaway is that it takes time and resources to reestablish and reorient supply links both offshore and onshore.

The challenges in establishing new supply links are illustrated in Ford Motor Company’s public comments to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) with respect to tariffs being imposed on certain types of graphite, a critical input in batteries for electric vehicles (EV).4 The company describes that “[t]here currently are very few alternative sources for graphite used in EV batteries [...]. As a result, the current application of Section 301 tariffs to imports of certain graphite [...] will create substantial challenges for EV production [...]. Ford still must use Chinese secondary particle graphite almost exclusively for the downstream domestic manufacture of EV batteries, a growing sector that faces substantial competition with non-U.S. battery producers. In this environment, USTR’s proposed modification – coupled with the recent exclusion expirations – will harm U.S. interests instead by undermining domestic production of EVs and EV batteries.”

Getting the basic facts right on the structure of U.S. industry is fundamental to assessing the impacts of tariffs. An examination of the contribution of U.S. goods trading firms to exports, imports, and employment, using the latest publicly available information, reveals that exporter-importer firms play an outsized role in U.S. goods exports and manufacturing job growth.

Exporter-importer firms are responsible for the overwhelming majority of U.S. goods trade

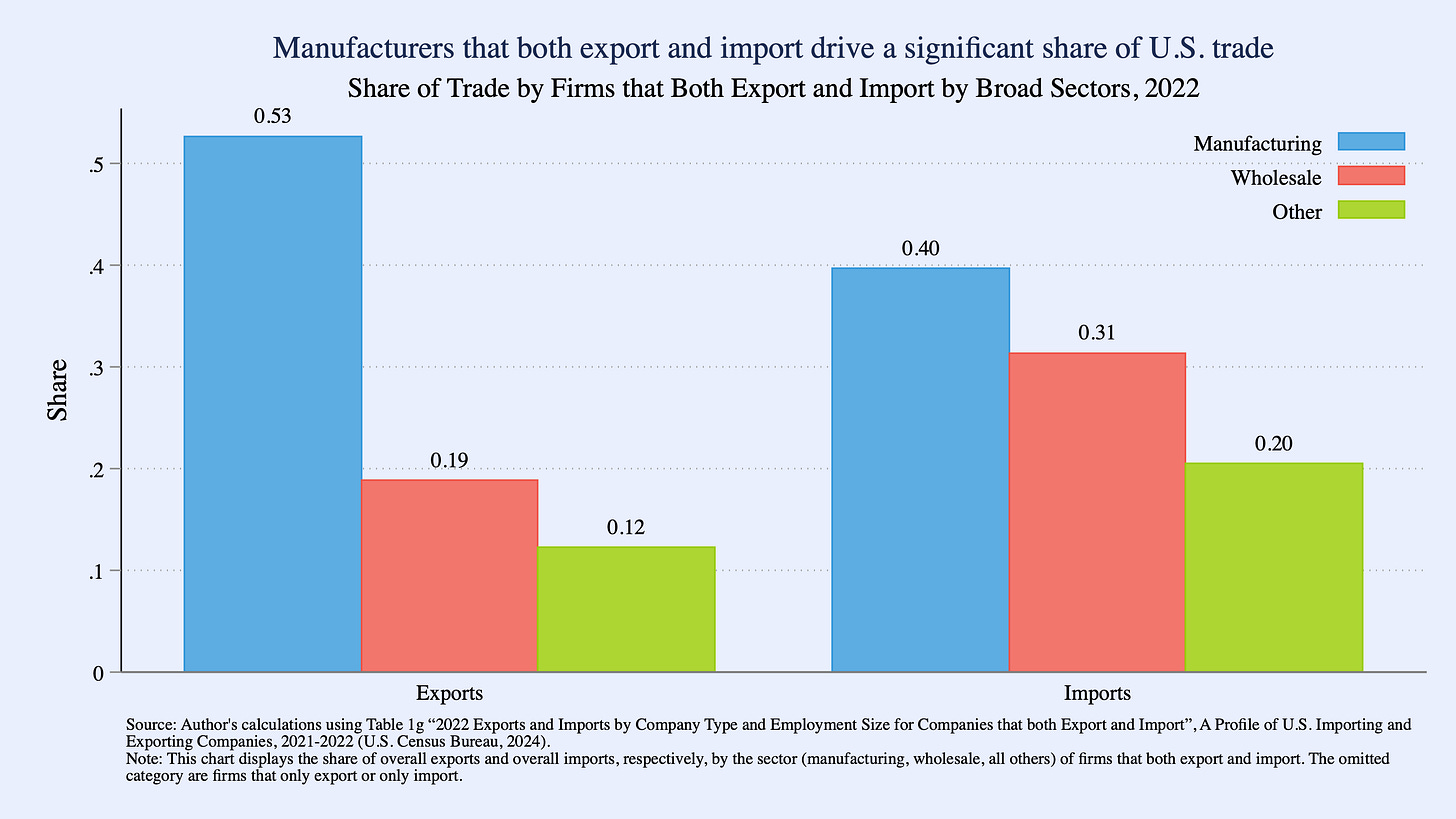

Firms that both export and import goods account for 84% of the total value of exports and 91% of the total value of imports.5 Manufacturers that both export and import represent half of all exports and 40% of all imports, underscoring the complementarities between exports and imports in U.S. production.6

Exporter-importer firms are major employers across all industries

U.S. firms that trade in goods account for half of all jobs in the economy. However, trade participation by U.S. firms tends to be rare: goods traders account for less than 10% of all firms and less than a quarter of all establishments in the economy.

Firms that both export and import are even rarer but employment at goods traders is concentrated in exporter-importer firms: 2 out of 5 jobs in the economy.

Exporter-importer firms have a diverse industrial footprint employing workers not only in the manufacturing sector but also across service-providing sectors. Exporter-importers employed more than 80% of all U.S. manufacturing workers (i.e., 4 out of 5 manufacturing jobs) and over half of all workers in the management, utilities, wholesale, transportation, information, and retail sectors. Exporter-importers’ substantial employment shares in services-providing industries reflect a shift by manufacturers to increasingly sell services.

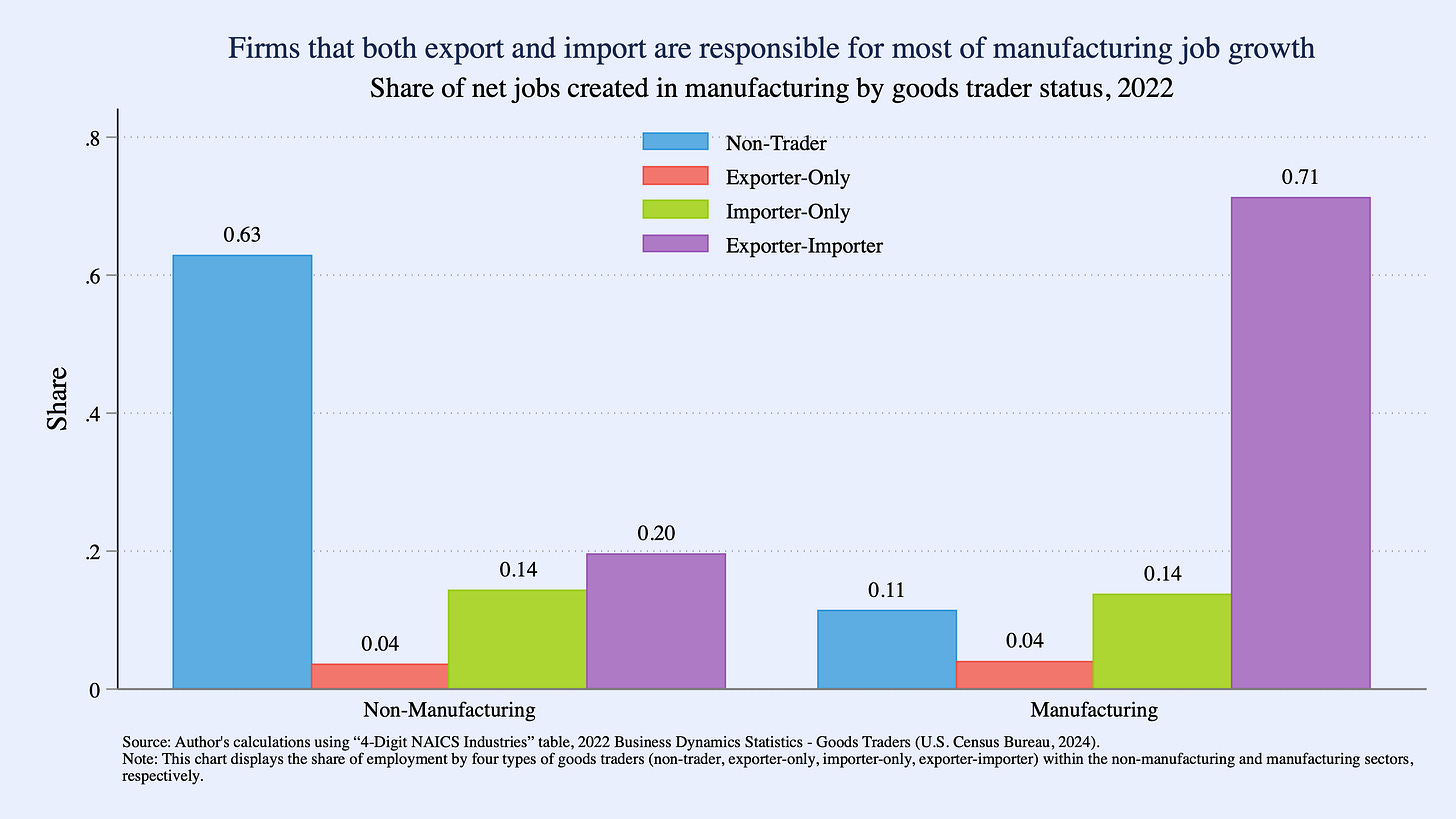

Exporter-importer firms contribute disproportionately to manufacturing job growth

Exporter-importer firms are not only major employers but also the largest net job creators in the manufacturing sector.7 Over three-quarters of all net new jobs created in the manufacturing sector are by exporter-importer firms.

Broad-based tariffs hurt exports through supply chain linkages

Firm participation in international markets along both the importing and exporting margins highlights the interdependence of imports and exports. The concentration of imports at exporter-importer firms suggests that tariff-induced cost shocks are most likely to directly impact exporter-importers.

This is borne out in evidence from co-authored work examining the impacts of the 2018-2019 import tariffs on U.S. exports. Three facts underscore the links between exports and tariff-impacted imports: (i) 57% of all imports facing tariffs were intermediate goods; (ii) exporters exposed to import tariffs accounted for 84% of total exports; and (iii) the average importer in the manufacturing sector paid implied duties of about $1,600 per worker (equivalent to about 1.5% of the average wage bill) and employed 65% of manufacturing workers. By 2019, the negative effect of import tariffs on exports is equivalent to what would happen with a direct ad valorem tariff on U.S. exports of 2%. The analysis further indicates that export growth reductions would have been a third smaller if the new import tariffs were not levied on goods likely to be part of the average firm's supply chain.

U.S. tariff actions should be reassessed to minimize unintended hits to American competitiveness

Given exporter-importer firms’ outsized contribution to exports and as a major source of employment and job creation not only in the goods-producing sector but also across a wide range of industries in the service-providing sector, the continuation of existing tariffs and further broad-based increases are likely net hindrances to long-term U.S. competitiveness.

As U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said in his October 23, 2024 speech “[w]e know that indiscriminate, broad-based tariffs will harm workers, consumers, and businesses, both in the United States and our partners. The evidence on that is clear.” More importantly, he notes that “[m]eaningful shifts in policy require constant iteration and reflection.” The next administration should reassess the evidence and recalibrate U.S. tariff policy to ensure it supports overall American exports and manufacturing jobs.

This note focuses on an important driver of the negative impacts of broad-based tariffs on exports and employment in the manufacturing sector, however, broad-based tariffs could also negatively impact consumer welfare. The latest evidence indicates that both U.S. producers and consumers bore the brunt of the 2018-2019 tariff hikes.

For a summary of the impacts of the 2018-2019 tariffs on various economic outcomes see Redding (2023).

Calculated using 2023 import values from “Exhibit 10. Real U.S. Trade in Goods by Principal End-Use Category Chained (2017) Dollars,” U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services (FT900), August, 2024, U.S. Census Bureau (2024).

These are part of the public comments submitted in response to USTR’s “Request for Comments on Proposed Modifications and Machinery Exclusion Process in Four-Year Review of Actions Taken in the Section 301 Investigation: China's Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation.” (89 FR 46252).

Calculated as a share of known goods trade value (i.e., the portion of total trade that could be matched to specific companies) using the most recent available data in 2022 (Census Bureau, 2022).

These statistics potentially understate the reliance of U.S. manufacturers on imports since they do not include producers who purchase goods from intermediaries that import directly.

Nicely argued. I make a related argument at

https://thomaslhutcheson.substack.com/p/tariffs

excellent!