The financial status of entitlement programs: what the headlines miss

The annual financial reports of Social Security and Medicare rely on long-term assumptions that are hard to forecast – but may be overly optimistic

The Social Security and Medicare programs each operate through a trust fund, which takes in revenues and pays out benefits. Each year, designated officials acting as trustees of these funds release a report that communicates the current and projected financial status of the two programs. These reports are important because they help policymakers understand whether changes to the program are needed in order to restore financial health to the programs.

The Social Security and Medicare trustees have found that the programs face a shortfall over a 75-year horizon for several years. This year’s report projects that the Social Security trust fund will become exhausted by 2035, and the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund will run out by 2036. However, Congress has repeatedly failed to answer the call to action, and each subsequent report tends to find that the program is in worse shape than before.

When the 2024 reports were released on May 6, 2024, headlines were mixed. The AP declared it as a “measure of good news” because the dates of exhaustion for Medicare’s trust fund and Social Security’s combined (old-age, survivors and disability insurance) trust fund were pushed back by five years and one year, respectively. The New York Times similarly celebrated: “Strong Labor Market Steadied Social Security and Medicare Funds.” However, the Washington Post had a more pessimistic view, stating “Social Security and Medicare finances look grim as overall debt piles up,” while the Wall Street Journal urged readers, “Social Security Funds Are Running Dry. Don’t Panic.”

Here, we review the reports’ findings, investigate the changes in the long-term assumptions each program uses in their estimates, and assess their implications for the programs’ futures.

Social Security and Medicare face substantial deficits, and the year the trust funds are exhausted only tells part of the story

While most media reports focus on the date of trust fund exhaustion, the trustees also report the actuarial balance over a 75-year period, which is the difference between the income the trust fund is expected to receive and the costs the trust fund is expected to pay, expressed as a percentage of taxable payroll (i.e., all of the earnings subject to payroll taxes). This measure is more nuanced than the exhaustion date, which doesn’t provide information regarding the trajectory of net spending after the balance turns negative.

There are three main trust funds that operate as separate legal entities: one for old-age and survivors insurance (OASI), one for disability insurance (DI), and one for hospital insurance (HI).1 The trustees also report exhaustion dates and actuarial balances for the combined old-age, survivors and disability insurance (OASDI), though neither trust fund can operate with a negative balance independently under current law.

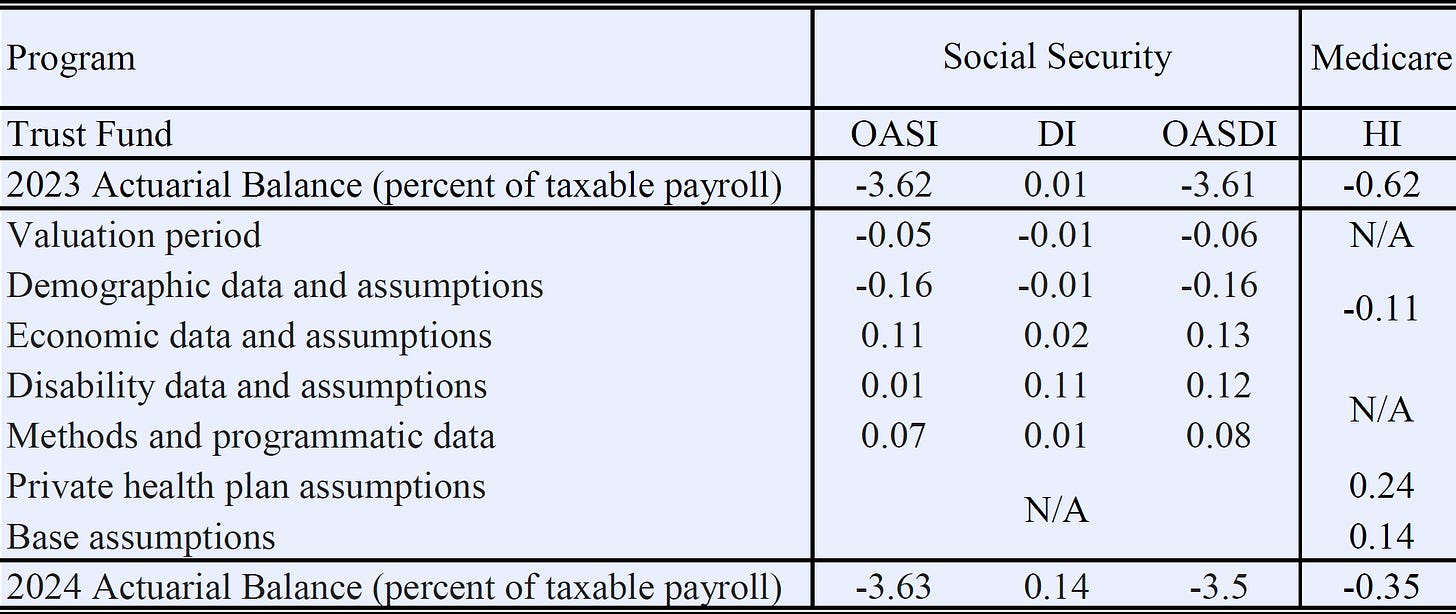

These four actuarial balances from the 2023 report and the 2024 report, with an accounting of the difference between the two, are shown in Table 1. The table shows that while the financial status of the OASI trust fund, which pays retirement and survivor benefits, held steady on net, the actuarial deficit of 3.63 percent of taxable payroll remains large in absolute terms. The DI and HI trust funds both saw their financial status improve, but the HI program still faces an actuarial deficit of 0.35 percent of taxable payroll.

In total, the actuarial deficit in the three trust funds based on the 2024 trustees report is 3.85 percent of taxable payroll. This means that bringing the programs into balance over the 75-year horizon would require increasing payroll taxes by 3.85 percentage points, a level 25 percent higher than the total tax currently levied on employers and employees for both programs (15.3 percent).

Table 1: Actuarial balances for disability insurance and hospital insurance improved since 2023, but were steady for old-age and survivors insurance

Source: Summary of the 2024 Annual Reports, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/trsum/.

Demographic, economic and programmatic assumptions heavily influence measurement of the actuarial balance

The trustees face the unenviable task of making predictions about a wide variety of demographic and economic assumptions well into the future. Both funds receive their primary source of income from a payroll tax levied on earnings, so the financial status of these programs is closely tied to the size of the workforce, labor force participation rates and the overall health of the economy.

Demographic assumptions

The largest shift in demographic assumptions was to the long-run total fertility rate of 1.9 children per woman, down from 2.0 assumed in the 2023 report. This change worsens the financial picture of the program because lower fertility rates mean fewer workers in the future supporting each retiree. Not only does this change increase the Social Security actuarial deficit by 0.16 percent of taxable payroll, but it also impacts Medicare’s financial status because of its reliance on payroll taxes for revenue.

There is reason to believe that even this assumption for long-run fertility rates may be overly optimistic. As shown in Figure 2, fertility rates have been in decline since 2007, and hit a new record low of 1.616 births per woman in 2023. A total fertility rate of 1.9 has not been seen since 2010, and for fertility rates to increase to that level in the window assumed would require women aged 30-39 to have children at rates not seen since the baby boom. A realization of fertility rates even slightly lower than those built into these projections will substantially worsen the financial status of the program. If, for instance, fertility rates remained at 1.6 children per woman, the actuarial deficit for Social Security would increase from 3.5 percent of payroll to 4.2 percent.

Figure 2: Social Security and Medicare Trustees project fertility rates will rebound, but the recent downward trend shows no signs of reversal

Source: Social Security 2024 Trustees Report, Table V.A1, Fertility and Mortality Assumptions, https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2024/lr5a1.html

Economic assumptions

The long-run assumptions for productivity, prices, average covered wages, interest rates, and unemployment have not changed since the prior year’s report. However, in the short run, the trust fund’s finances improved because of higher real wage growth assumed over the near term, leading to higher payroll tax collections relative to benefits than in last year’s report. This change amounted to an increase in the actuarial balance by 0.11 percent of payroll, counteracting the worse news from lower long-run fertility rates.

Disability assumptions

Additional assumptions regarding disability incidence, disability death rates, and recovery rates from disability are needed to project the payout of the disability insurance part of Social Security. Due to a reduction in disability incidence since 2010, and the recent increase in employment among disabled workers (possibly due to more telework opportunities), SSA has assumed lower disability incidence rates and higher recovery rates in the current report. These two changes combined improve the actuarial balance by 0.12 percent of payroll, a significant increase.

While recent trends suggest these changes may be warranted, there are other data that suggest caution is warranted. The share of the population reporting disabilities has increased, reversing a long declining trend. The increase is especially pronounced among working aged populations age 25-54, and seems to be driven by increases in the share reporting cognitive difficulties. The share of the population currently experiencing long Covid symptoms is thought to be approximately 7 percent, though these data suffer from low response rates. While unclear as to how the prevalence of long Covid will change in the months and years ahead, recent work by Goda and Soltas indicates that Covid-related work absences result in persistent drops in labor force participation, with long Covid as a possible mechanism.

Drivers of Medicare’s financial status

As shown in Table 1 above, the main driver of the increased actuarial balance for the Medicare trust fund was private health plan assumptions, which improved actuarial balances by 0.24 percent of taxable payroll. Payments to Medicare Advantage (MA) plans (private health insurance plans that Medicare enrollees can choose in lieu of traditional Medicare) now reflect a change in how medical education is accounted for and an updated risk adjustment model which together slow the growth of MA payments in all future years.

The second largest change was an update of the projection base (+0.14). This adjustment reflects the fact that 2023 Medicare expenditures were lower than expected due to higher payroll tax income (+.05) and lower expenditures (+.09).

In 2020, CMS implemented a time-to-death (TTD) adjustment to demographic factors in the model. This adjustment was motivated by the idea that, if mortality continues to improve, a greater proportion of beneficiaries at any given age are further from death than in prior years. As Medicare spending per enrollee is strongly correlated with proximity to death, the TTD adjustment results in lower projected spending and improved financial health of the Medicare program.

This assumes that the additional life years gained are healthy years, but some research has challenged this notion of healthy aging. Crimmins & Beltrán Sánchez (2011) and Beltrán-Sánchez, Jiménez, Subramanian (2016) showed that while length of life is increasing, additional lifespan is subject to morbidities and disabling conditions. If this is the case – that we are living longer at a worse state of health – the TTD assumption may not fully hold, which would result in Medicare’s financial status being worse than predicted.

Recent changes: The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and Covid-19

The 2024 Medicare trust fund report was heavily influenced by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 due to provisions that restrain price growth and negotiate drug prices for certain drugs, and those that change the design of Medicare’s prescription drug benefit to reduce out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries. In particular, the trustees assume that the IRA will decrease per capita spending on Part D drugs by 0.2 percentage points (relative to national health expenditures) while keeping spending growth rates for Part B drugs the same.

The Medicare program was strongly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic due to spending on testing and treatment for Covid-19, expanded telehealth, and the decline of non-Covid-related care. While the public health emergency has stabilized, they have continued to adjust for morbidity improvement in the surviving population and lower-than-normal home health spending, which is expected to reverse in the next three years.

Analyzing current law paints a rosier view of Medicare’s financial stability

It is important to note that the mandate of the Trustees is to assess whether the financing provided under current law is adequate to cover the benefit payments and other expenditures required. However, current law assumes that the gap between Medicare payment rates and payment rates from private insurers continues to grow to unsustainable levels: By the end of the long-run projection period, it is estimated that Medicare payment levels for inpatient hospital services will be less than 40 percent of the corresponding level paid by private health insurance.

As Medicare’s payments for health services fall increasingly below providers’ costs, many would stop serving Medicare beneficiaries. Therefore, it is likely that Congress would face pressure to prevent beneficiaries’ access to Medicare-participating physicians from deteriorating over time. Given the likelihood of legislative action, the report provides an “illustrative alternative” section in the appendix that is likely the most accurate estimate of cost, which is substantially higher than those used in the main section of the report.

The actuarial deficit for the 75-year projection window from the illustrative alternative is 1.17 percent of taxable payroll, substantially larger than the current law estimates of 0.35 percent. The differences are not as large when forecasting over a shorter period, illustrating that the gap between current law and the illustrative alternative is bigger as time goes on.

What does this mean for the future of Social Security and Medicare?

We have known that entitlement programs face shortfalls for quite some time, and there is nothing in this year’s reports that indicate anything markedly different. As the year the trust funds are exhausted approaches, this metric is a salient reminder that these programs need fixing. However, the actuarial balance tells us more about the scope of the problem and the way that different realizations of the future can impact the path of income and expenditures for these programs.

There are reasons to believe that the assumptions built into the current projections are overly optimistic. In particular, fertility rates have not rebounded since the Great Recession and appear to be a more structural shift in childbearing than previously thought, and are a big driver of income through payroll taxes. This could have important implications: if actions are taken to address the shortfall that do not account for its size appropriately, further action will be needed at a future date.

All projections are inherently uncertain. It is exceedingly unlikely that all of the assumptions made to model income and expenditures will play out as projected. The focus of reforms should be on not only addressing the shortfall – but also on ensuring that entitlement program financing is resilient to changes in economic and demographic conditions.

There is also a trust fund for Supplemental Medical Insurance (SMI). This fund is considered to be adequately financed into the indefinite future because, unlike the other trust funds, its main financing sources are enrolled beneficiary premiums and federal contributions from the Treasury, which are automatically adjusted each year to cover costs for the upcoming year. The trustees state, “Although the financing is assured, the rapidly rising SMI costs have been placing steadily increasing demands on beneficiaries and general taxpayers.”

Thanks for the overview, and details. Small item but big for readers' quick(er) comprehension!

"bringing the programs into balance over the 75-year horizon would require increasing payroll taxes by 3.85 [[percent*age points* on top of the current 15.3% (half of which is paid by employers) — a 25 percent increase. (This is assuming there are no other, more specifically targeted revenue increases, such as removing the contribution cap on high earners.)"]]

Thx.