The effect of online interviews on the University of Michigan Survey of Consumer Sentiment

Negativity among online respondents is dragging sentiment down by nearly 9 index points

We analyze the University of Michigan’s (UMich) Consumer Sentiment survey’s (“sentiment”) recent change in survey methodology from collecting interviews via phone to collection via the Internet. We document several features of this new sample that we believe are materially affecting the results of the survey. While we agree with UMich’s own analysis that the online interviews themselves display similar trends across time as phone interviews, we believe online respondents are resulting in the level of the overall sentiment and current conditions indices being meaningfully lower, making more recent UMich data points inconsistent with pre-April 2024 data points. Specifically, we use a simple statistical model to estimate that the effect of the methodological switch from phone to online is currently resulting in sentiment being 8.9 index points –or more than 11 percent–lower than it would be if interviews were still collected through the phone. We validate this estimate through comparison with an independent third-party survey. The mechanism for this bias primarily runs through the “current conditions” questions, especially on durables and personal finance experiences, rather than through the “expectations” questions. We also observe ample evidence of survey respondents exhibiting less engagement by providing less rationale for their answers. While further analysis is needed to understand these dynamics, we believe that differing survey demographics between online and phone respondents, in addition to the modality of online surveys itself, may be causing this gap.

Switching to online responses has created a structural break in sentiment

One of the enduring mysteries of the pandemic is, “Why are people so down on the economy when the underlying data are so strong?” In February 2020, the University of Michigan (“UMich” for the rest of this piece) index of consumer sentiment stood at 101, above the 90th percentile of the historical distribution. In October 2024, despite a low 4.1 percent unemployment rate, strong retail spending, and inflation that has largely returned to target, the index stands at 68.9, in the 15th percentile of the historical distribution and well below where we would predict given pre-pandemic relationships with key economic data. For reference, the index level is now lower than it was 15 years ago in September 2009, when the economy was barely emerging out of the recession brought on by the global financial crisis and the unemployment rate was 9.8 percent, more than double its current value.

This analysis doesn’t seek to explain all or even most of this broad mystery.1 Instead, it focuses on a narrow slice of it that has arisen over the last six months. This portion revolves around a change in how we measure consumer attitudes.

Due to the increasing costs of collecting surveys through the phone as well as a desire to ensure that the sample is representative, in April 2024 the UMich Survey of Consumers officially began incorporating responses from the web via a mailer that contained both a link and a QR code that would link a respondent to the survey. UMich had been piloting this survey change for a time beforehand but had not yet incorporated online responses into their official survey data. The transition was completed over the course of April, May, and June 2024 such that in April 2024, roughly 75 percent of responses were collected through the phone, while 25 percent were collected online. In May these numbers shifted to 50/50, and in June, online and phone percentages were 25 and 75, respectively. Finally, in July all surveys were conducted through the online method.

During the transition, there was a noticeable fall in the survey’s flagship index of consumer sentiment. This fact alone is not dispositive. The index can fluctuate meaningfully from month to month, especially in presidential election years like 2024 since consumer sentiment is susceptible to political polarization. As part of the transition, UMich survey staff analyzed the differences in survey modality between phone and online respondents and concluded that trends between both survey modalities were largely similar. We also find ample evidence in support of their conclusion. In this analysis, however, we find that the levels are different.2 Therefore, the index level suffered a structural break in April 2024. Among other things, this break makes the index apples-to-oranges between post-June 2024 and pre-April 2024.

Online respondents are older and feel more negatively about current economic conditions

Our first question cuts straight to the chase. In the phone-to-online transition months between April and June 2024, was there a statistically significant difference in the levels of overall sentiment, current economic conditions, and expectations between phone and online respondents of similar backgrounds?

A key initial subquestion is whether online status was, in practice, demographically unbiased in those pooled months. Thankfully, UMich allows us to answer this question by making anonymous microdata of its survey responses publicly available. This allowed us to compare the online and phone respondent populations in those transition months of April to June 2024. A cursory look at the weighted age distribution of phone and online assignments suggests that, no, they were not random in practice. For example, online respondents were more likely to be older in those transition months, which might affect their sentiment responses.

A more formal multilevel logit model–which measures the likelihood of an individual being in a certain age cohort after accounting for other demographic factors–confirms this difference. Respondents 65+ for example had a 52 percent chance of being in the online group in April-June, which is more than twice as likely as respondents 18-24, and this difference is statistically significant (see the full results in Appendix Tables 1 and 2). This does not invalidate any analysis of the online effect on sentiment, it merely shows that demographic controls are necessary.

With this in mind, for every individual i in month t between April and June 2024, we build a model of sentiment of the form:

Where s is the index of consumer sentiment (“ICS”), online is a dummy equal to 1 if the individual is in the online sample, and V is a vector of controls.345 The model is estimated using OLS with robust standard errors. Here, the γ coefficient is the parameter of interest in our model, as it represents the effect on sentiment of being in the online group after controlling for other demographic characteristics. The estimated effect is -8.86 points to the sentiment index, an effect that is significant at the one percent level.

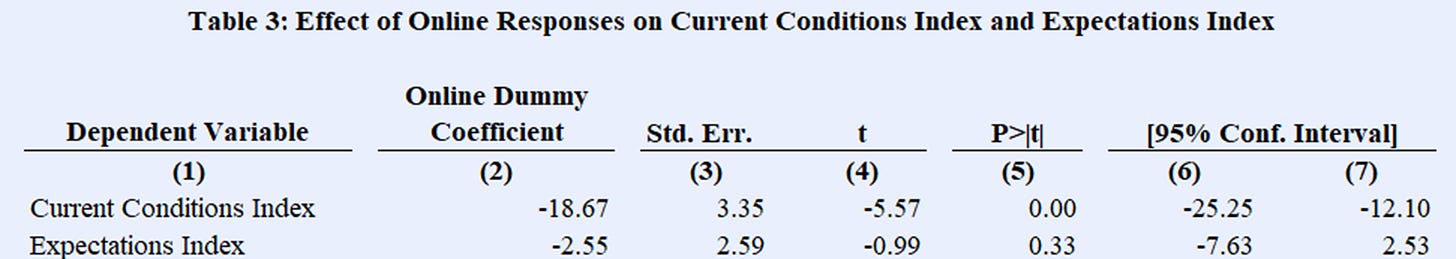

In addition to the topline consumer sentiment, UMich also produces two subindices which measure consumer attitudes about current economic conditions (“current conditions index”) and expected future economic conditions (“expectations index”). To examine if online respondents are more dour about the current economy or what they expect the economy to be like, we run the same model against each subindex in turn. The effect of being in the online sample against the current conditions index is a substantial -18.67 points, with even greater statistical significance than against overall sentiment. But against the consumer expectations index, the effect of being in the online sample is only -2.55 and not significant. This suggests that taking the Survey of Consumers online primarily affects the final index through the respondent’s assessment of current conditions, not through their expectations.

Attitudes about personal finances and buying conditions drive negative views of current conditions

When we decompose the index into its five relevant questions, we find that online respondents are dragging down sentiment primarily through more negative answers about conditions for durable goods and personal financial conditions. During the three month period from April-June 2024–when both online and phone responses were collected–the difference between online and phone respondents for these two questions are substantially large. This is presented in Figure 1 below.

As the figure shows, the net (weighted) difference between those that say it’s a good time to buy durable goods and a bad time to buy is roughly 18, 24, and 26 points worse in April, May, and June, respectively for online respondents than it is for phone respondents. Put differently, this means by June, online respondents were nearly 30 percent more negative in their assessment of buying conditions than phone respondents. Similarly, the net (weighted) differences between “better now” and “worse now” for personal financial conditions relative to last year are roughly 12, 19, and 21 points. Importantly, these spreads seemed to grow for these two variables as the online respondent share grew.

There are two other interesting features about this decomposition. First, the opinion of individuals about their personal financial conditions one year hence was also more negative for online respondents, although this difference did not consistently get worse like durable buying conditions or their current personal financial conditions. Second, business conditions over the next five years appear to have an upward bias for online respondents despite an otherwise negative bias for every other variable, although this positive bias shrank as more respondents went online.

Increases in “Not Applicable” (NA) responses suggest less engagement among online respondents

When digging into what is causing the bias in several index subquestions, we analyzed the reasons individuals gave for their answers. For durable goods buying conditions, one notable response as to why respondents believed what they did about buying conditions was simply the increase in “NA” responses. Table 4 below shows the top 10 responses from both the online and survey interviews for a question that asks respondents why they answered the way they did for durable goods buying conditions.6 For the phone sample, NAs represented less than one percent of responses, with only five respondents out of the 1,327 over the period giving such a response. In stark contrast, in the online survey, NA was the second most frequent response option.

Indeed, the share of online respondents stating NA as their answer increased over the three months among the online group. Interestingly, however, among respondents who selected “NA” as an option, the share of those who thought buying conditions were good relative to poor was almost exactly even: 99 to 100, respectively (with one NA response saying the same).

The data look largely similar for questions asking why respondents feel the way they do about their income relative to one year ago.7 Here, we see six percent of online respondents (84 in total) selecting NA, while 0.1 percent of phone respondents (2 in total) select NA. Among those who selected NA, though, 27 believed their personal financial situation was “better now” compared to 18 who believed it was “worse now.”

These results suggest that online respondents appear to be less engaged, or at a minimum less willing to justify their answer. Importantly, though, our analysis cannot answer why online respondents are more negative. But these findings are consistent with other studies which have also examined online vs. phone sampling. For example, in 2015, Pew Research Center–a gold-standard polling organization–noted that in a political survey “[p]eople expressed more negative views of politicians in Web surveys than in phone surveys.” The hypothesis put forward by Pew, which we find credible evidence for as well, is that “when people are interacting with an interviewer, they are more likely to give answers that paint themselves or their communities in a positive light, and less likely to portray themselves negatively.”

The UMich index diverges from methodologically consistent measures of sentiment

As a final exercise, we revisit our original motivating regression, and use the results to create an adjusted consumer sentiment index that represents an apples-to-apples methodology over the entire sample. Since all UMich respondents are online now, the adjustment to all new UMich consumer sentiment datapoints after June 2024 is straightforward and simple: our adjusted series in each month after June is simply higher than the official series by the absolute value of the online respondent effect, or 8.86 points. The adjustment in April to June is less than this since those months included less than 100% of online respondents. Table 5 below shows the official and adjusted series month-by-month for 2024.

For independent validation of our adjustment, we look to Morning Consult, a U.S. business analytics firm that has been running its own daily Index of Consumer Sentiment since January 2018 with near-identical questions to the UMich survey. Unlike UMich, however, Morning Consult has stayed consistently online throughout its existence. Since we model online bias as simply a level shift in outcomes, Morning Consult’s online methodology isn’t an issue. By rebasing their index, we can offset any possible online bias in their survey and take advantage of their consistent, uninterrupted methodology. We standardize the Morning Consult index and recast it with the same mean and standard deviation as the UMich index over January 2018 to March 2024 (the period running from the start of the Morning Consult series to just before the UMich online transition). The resulting UMich-consistent Morning Consult index is shown in green, while actual UMich sentiment is in blue and our adjusted-sentiment series is in orange. Beginning in April 2024, the Morning Consult index follows our adjusted index almost exactly rather than the official UMich index. This supports the conclusion that our model and our adjustment do reasonable jobs of isolating the post-March 2024 bias among UMich online respondents.

As our analysis suggests, a simple way for UMich to solve for online bias is to add 8.9 to each new read of the index of consumer sentiment. There is precedent for such a level adjustment: since the early 1970s, UMich has applied a constant to the sentiment, current conditions, and expectations indices every month to account for a sample design change that took place in the 1950s.

The negative bias of online respondents has been dragging down sentiment when it likely would otherwise increase

The shift to online interviews appears to be lowering the level of the UMich consumer sentiment index by 8.9 points. This is consistent with the independent Morning Consult Index of Consumer Sentiment, which did not change methodologies over April-June, suggesting what an apples-to-apples UMich sentiment index would have shown in the absence of a methodological change.

The timing of the methodological transition relative to other macroeconomic events, particularly inflation, is also important. In April, when the transition began, annual headline CPI inflation was 3.4 percent. As of September (the last month for which we have data), it was 2.4 percent–falling roughly 100 basis points in the course of five months. In addition to real-time inflation, the impact of elevated price levels is also decreasing. As our analysis shows, during this period, some of the potential gains to sentiment from these dynamics were largely eroded by the increasing share of online respondents.

The channel through which online respondent negativity appears to be primarily the current conditions questions, i.e., durable goods and past year personal finances. On durable goods in particular, online respondents appear to be significantly more likely to answer “NA” than phone respondents as a reason for their views on durable buying conditions, perhaps suggesting a less engaged online sample. The combined result of this analysis also adds to other studies which show that online respondents possess a negativity bias, potentially resulting from not interfacing with another human when taking the survey.

Appendix

For works attempting to understand this gap in detail, see Cummings and Mahoney (2023a), Cummings and Mahoney (2023b), Ip (2023), and Harris and Sojourner (2024), among others.

UMich estimated a priori at the start of the transition period in April 2024 that the method effect of switching to online collection would total -6.6 points to the level of the overall index of consumer sentiment, and -13.6 points to the index of current economic conditions (see page 29). Despite this, UMich did not subsequently adjust their indices post-March 2024 to keep each series internally consistent over time. There is precedent for such an adjustment: the index of consumer sentiment, the index of current economic conditions, and the index of consumer expectations all to this day have constants added to them by UMich to account for sample design changes in the 1950s. Our point estimates for the method effects are larger than UMich’s initial estimates in both cases.

Controls include month fixed effects, sex*age interactions (12 categories), sex*marriage*parental status (8 categories), sex*education (12 categories), sex*political affiliation (6 categories), homeownership, region (4 categories), and individual’s month in the survey rotation sample (1st, 2nd, or 3rd).

We chose demographic dimensions that we found to be unevenly balanced between online and phone respondents over April and June 2024. Some important characteristics that we tested turned out to be balanced and thus we left out of the analysis. For example, there were no significant differences in income tercile shares between online and phone in April-June 2024.

We also tested for month*online interaction effects, which were not significant over April to June. In the absence of any evidence to the contrary, we model online effect as level effects on sentiment without seasonality, but we would like to see more data before entirely dismissing the possibility of seasonality in online effects.

In the UMich microdata, these are responses to the “DURRN1” variable.

In the UMich microdata, these are response options to the “PAGOR1” variable.

Lots of great info in this article about the history of the Index of Consumer Sentiment. I learned a lot. Index of Consumer Sentiment (ICS) data shows the extent of the no-recession vibecession in 2021-22. Steep plunge in ICS as inflation rose. 2021-22 vibecession ICS readings not affected by recent change in survey methodology.

Adjustment to recent ICS readings by Cummings and Tedeschi shows that vibecovery since 2021-22 vibecession stalled this year, but vibes have not slipped backwards. No sign of another vibecession. That said, vibecovery has been relatively weak. ICS not yet back to previous peak of summer 2021. In my opinion, relatively weak economic vibes go a long way to explaining why Harris campaign is struggling.

Great stuff! I do worry that correcting this mode bias with an intercept shift, especially if UMich restates the past several months of data, would be conspiracy theory fodder. (“Rigging the data”, etc)