Quick hits: things we're thinking about

Gas prices, social security, a guaranteed income experiment, evictions, and wage growth

This week, we’re trying something inspired by responses to our reader survey from earlier this summer (respond now, if you haven’t already): brief discussions of things we’ve encountered recently that have influenced how we think about some policy issue. Let us know at the end if you would like to see more of this kind of post.

Gas prices are low, oil production is high

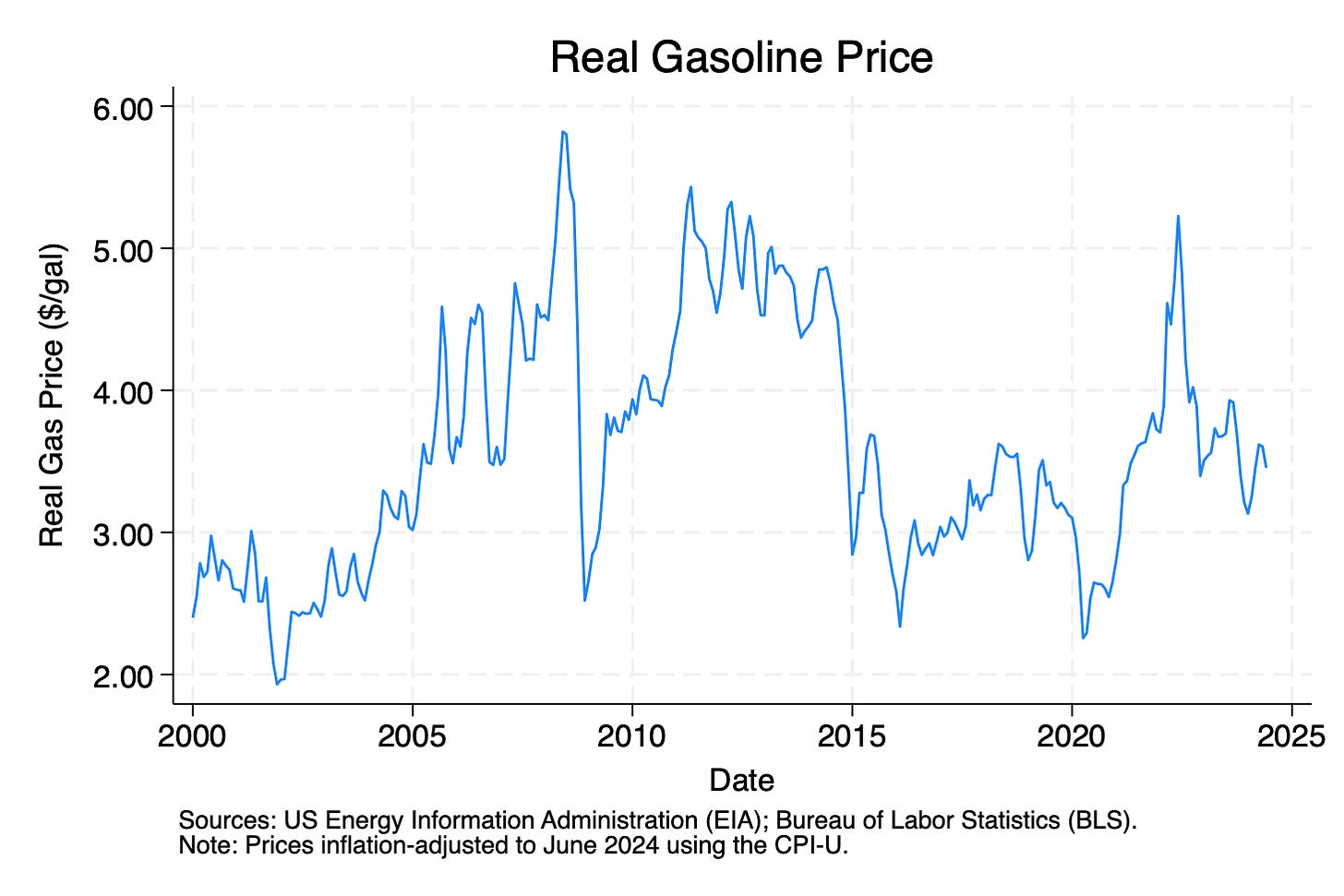

Gas prices are falling, with the national average down to $3.46/gal last Friday, August 9—not that you’ll be hearing about it on TV. (As we showed in a May Briefing Book price, TV rarely covers gas prices when they drop below $3.50/gal.) Indeed, real gas prices are lower than they have been 63% of the time this century.

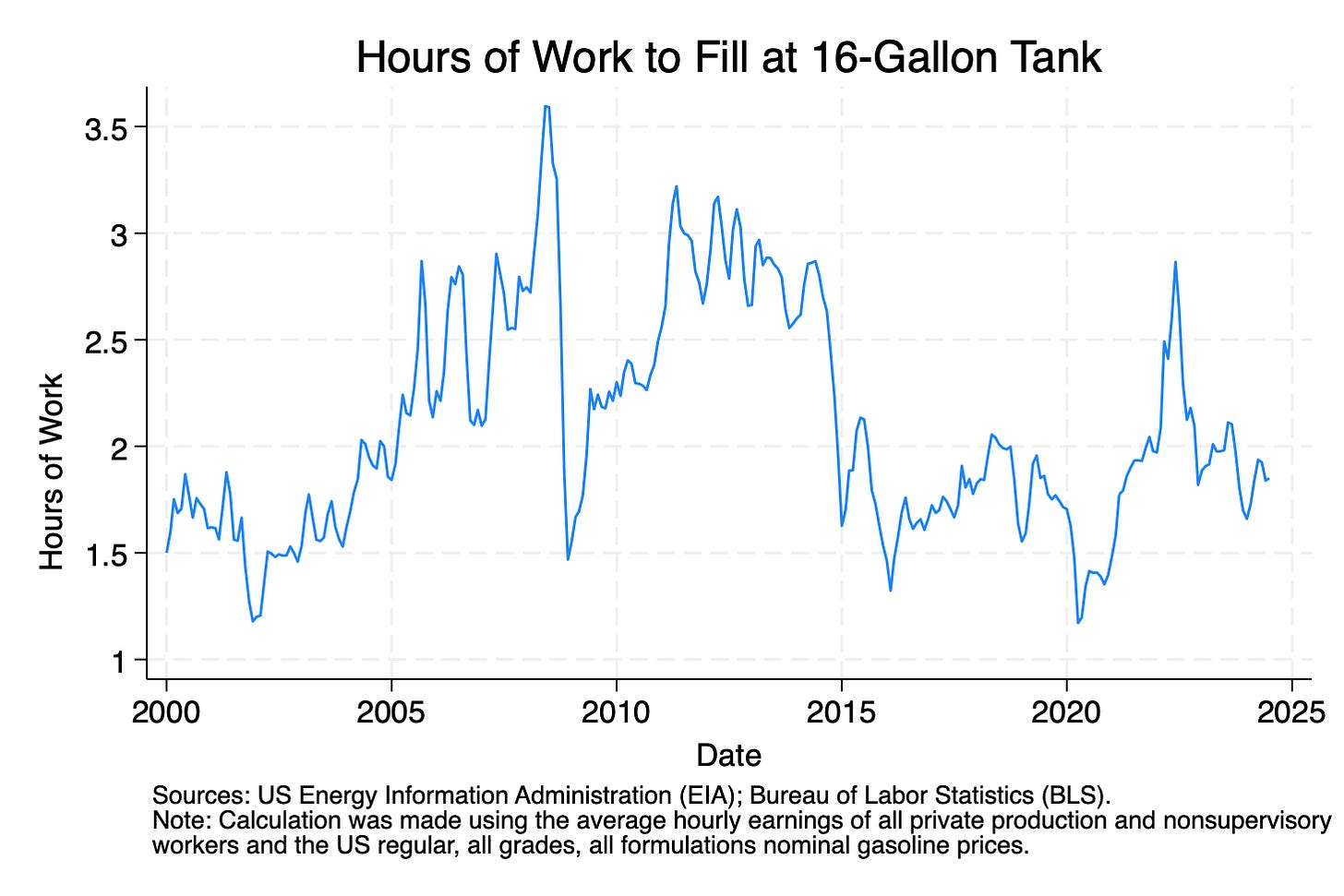

Put differently, today the average worker (production and nonsupervisory) needs to work 1.85 hours to fill up a typical car’s 16-gallon tank, fewer hours than at most times since the turn of the century (59% of the time, to be exact)

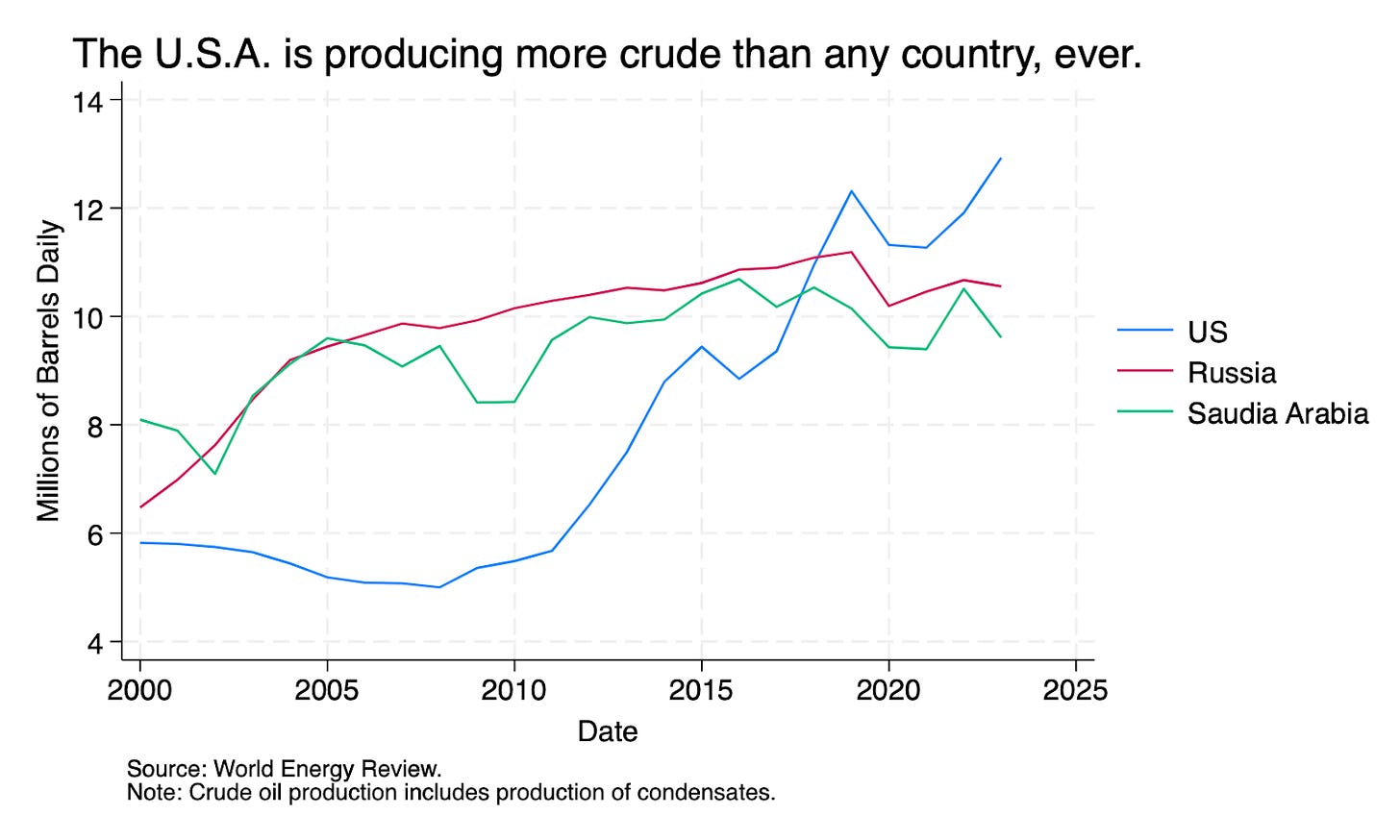

A key driver of the recent decline in gas prices is greater domestic crude production. The U.S. is now not only producing more than at any time in our history but more than any country has ever produced, ever. Importantly, the increased production is largely short-cycle shale, generating less long-run lock-in than offshore oil rigs. Combined with gangbusters clean energy investment, it gives me confidence in our ability to bridge to a clean energy future, while minimizing the disruption from high energy prices.

— Ryan Cummings

Who pays income taxes on their Social Security benefits?

The effects of collecting income taxes on Social Security benefits | JPubE 2018

Economics of Social Security Panel, "Earnings Inequality and Payroll Tax Revenues" | nber.org

Former President Donald J. Trump recently declared that seniors should not pay taxes on Social Security. But what do seniors currently pay? For nearly a half century, Social Security benefits were excluded from federal income taxation. This changed for the first time in 1984 after the 1983 Amendments to the Social Security Act came into effect and a portion of benefits became subject to federal income taxes, making them more in line with the tax treatment of other pension benefits.

The share of beneficiaries whose benefits are taxed has risen from about 10 percent in 1984 to over half today because the income thresholds that indicate whether benefits are taxable were not indexed to prices or wages. This is an important source of revenue to the program: estimates suggest that eliminating this provision would reduce revenues by $1.4-1.8 trillion, advancing the insolvency date of Social Security’s trust fund by 1-2 years. Additionally, virtually all of the tax savings would go to middle- and higher-income families since lower-income families pay little in taxes on their Social Security benefits to begin with. While some of these estimates incorporate the impact of a tax reduction on wages and growth, these estimates are small compared to the overall revenue impacts.

A recent panel discussed how growing earnings inequality has changed the share of income subject to Social Security payroll taxes, but the role of inequality in retirement income and the interplay with the taxation of benefits has not been fully examined. Policymakers should consider a wide range of possible reforms to the Social Security program, but eliminating the taxation of benefits moves the program further into insolvency without furthering other reform goals.

— Gopi Shah Goda

How do people respond to guaranteed income?

Universal Basic Income, or UBI, has been an intensely-debated policy idea for decades. A flat minimum benefit for households with few or no strings attached could simplify parts of our social safety net and make them easier for families to access. But a key uncertainty is the labor force trade-off: the income effects at both the intensive (fewer hours worked) and extensive (lower labor force attachment) margins. A recent paper by Eva Vivalt and co-authors, “The Employment Effects of a Guaranteed Income: Experimental Evidence from Two U.S. States” adds helpful insight into this potential trade-off. The paper draws on a three-year study in which a study group of 1,000 participants received $1,000 per month unconditionally and a control group of 2,000 participants received $50 per month.

The researchers found the effect of the program on labor outcomes was meaningful and significant. At the individual level, pre-transfer income fell by $1,500 per year for the study group (a 4% drop on average), hours worked fell by 1.3-1.4 hours per week, and labor force participation fell by 2 percentage points. At the household level, pre-transfer income fell by $2,500 to $4,100 (roughly 5%). The study therefore suggests that the labor force implications of UBI are a serious consideration. On the other hand, participants were still net-net better off post-transfer: by about $10,000 per year at the individual level and by $6,100 at the household level. So the study may also point to a path where elements of UBI can be combined with other policies or specific reforms—such as replacing high effective-marginal-tax-rate programs—to retain its simplification advantages while mitigating its labor market effects. More research is also needed at even longer timespans than this impressive study to capture the ways in which a perceived permanent UBI changes family behavior.

— Ernie Tedeschi

When do people get evicted?

I attended the NBER Summer Institute in late July. We’re in the midst of a purple patch of research on eviction, with recent papers deepening our understanding of the causes, consequences, and potential policy remedies, and I was eager to see Humphries, Nelson, Nguyen, van Dijk, and Waldinger's new working paper, “Nonpayment and Eviction in the Rental Housing Market”, which I’m summarizing below:

The authors obtained (very cool) payment and eviction data for 6,000 tenants in midwestern cities from 2015 to 2019.

Using the raw data, the authors show that landlords tolerate some nonpayment and many tenants who fall behind on rent eventually recover. Interpreting the data through the lens of a structural model, they estimate that landlords mainly evict tenants with persistent payment issues (although there is a non-negligible share who are experiencing more transitory shocks).

The upshot is that eviction mitigation policies—short-term rental assistance, procedural interventions, and an eviction tax—largely delay the inevitable. Since most otherwise evicted tenants are suffering from persistent shocks, temporary delay is not enough to get them back on their feet.

To be clear, these policies still have benefits. The delay allows the smaller share of tenants facing transitory shocks to get back on track. And everyone benefits from the delay. That said, eviction policies would have a larger benefit-cost ratio if targeted at the types of tenants (or during economic periods) where shocks are more transitory. Indeed, the literature on Chicago’s Homelessness Prevention Call Center – which explicitly targets temporary financial support to people facing transitory payment issues – finds salutary effects on use of homeless shelters, crime, and earnings for low income-earners.

— Neale Mahoney

Slowing wage growth is bad now?

The ongoing slowdown in nominal wage growth has mostly been celebrated as helpful in stabilizing inflation over the last 2+ years. But with inflation nearings its target and labor productivity growing faster than usual, further declines in nominal wage growth seem unnecessary.

Data from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for June showed declines in hiring and separations, both of which have been trending down since roughly the beginning of 2022. June’s declines put the churn rate, the sum of the hire and separation rates, at 6.6 percent, much lower than it typically is in a strong labor market. Gvien the 80.8 percent of prime-age workers who were employed, the churn rate would have been nearly 8 percent under the pre-pandemic relationship between those two measures.

The current churn rate is more in line with what we saw a decade ago, when the labor market was much weaker and gradually recovering from the Great Recession. In light of that, consider the relationship between churn and year-ahead nominal wage growth:

Current churn points to something like 2-3 percent nominal wage growth over the next year, a continuation of the recent slowdown and likely in line with little to no real wage growth. If we’re looking at a labor market that is no longer delivering gains for workers, it’s time to stop celebrating slowing wage growth.

— Kevin Rinz

Really like this format, thanks you!

Looks like a discontinuity when the Churn rate gets to 7.75% - wage growth becomes independent of Churn and the labor market gets Wild West crazy.

If we're looking to maintain a smooth and predictable labor market, best to keep below that level.