Local immigration surges did not swing the local presidential vote in 2024

Local immigration rates don’t explain election results, but they could show where the next administration’s immigration policies will have the most impact

Immigration loomed large in the presidential election. Immigration ranked high among voter concerns, with sharp partisan differences in views on immigration. The politics of immigration were both national but also highly localized, with debunked claims of Haitians in Springfield OH and Venezuelans in Aurora CO causing havoc in their communities.

And yet localized surges of immigrants had no relationship with the swing in the vote between 2024 and 2020, even though voters thought Trump would handle immigration better than Harris would.

There are several ways to measure recent local immigration; all are imperfect

To assess the relationship between local recent immigration and the 2024 vote, the hard part is measuring recent trends in local immigration. Having good estimates of recent local immigration may also turn out to be important for predicting the local effects of a possible sharp reduction in immigration or even widespread deportations.

There’s a big debate over how much immigration there has been nationally in recent years. For 2023, the Census Bureau estimated net international migration of 1.1m, based largely on an extrapolation from lagged survey data. In contrast, the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate was 3.3m, based on other survey data and Custom and Border Protection’s border encounter data, which started climbing in the spring of 2021, surged from the spring of 2022 to mid-2024, and has since declined. Although getting the national immigration estimate right is critical for policy decisions – including the Fed’s view on how tight or slack the labor market is – this debate remains unresolved.

Measuring immigration at the local level is even harder than at the national level, for two reasons. First, surveys have a much smaller sample of respondents in any one locality than for the nation overall, so any survey-based estimate of local immigration will be much less precise than national estimates. Second, it can be hard to know where immigrants move after they enter the country because there is very limited administrative data on domestic migration generally. State, county, and city borders are not patrolled, and movements across them are not tracked. Estimates of domestic migration come from Census Bureau survey data, Postal Service change-of-address forms, and IRS tax returns, but these data sources are lagged, incomplete, or not publicly available.

The data sources for local immigration are limited and all have shortcomings. I looked at three:

Census Bureau population estimates. Each year, Census estimates county-level population changes, broken down into births, deaths, net domestic migration, and net international migration. The international component is the hardest to measure; is based on lagged survey data from the American Community Survey; and gets subsequently revised. The latest available are for 2023, with the international component based on 2022 ACS data. My first measure is the sum of this level of net international migration in 2021, 2022, and 2023, relative to the 2020 population estimate.

Census Bureau American Community Survey. The American Community Survey’s Public Use Microdata Sample includes respondents’ birthplace, citizenship, and year of entry to the U.S. for people born outside the U.S. These microdata are available for 2023. However, the smallest geographic area reported is the Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMA), which have a minimum population of 100,000 and are therefore often larger than a county. I calculated the share of each PUMA’s population that is foreign-born and entered the U.S. after 2020, and then used a PUMA-to-county mapping to estimate the recent immigrant share for every county. For this measure, many small counties had to be assigned the value for the surrounding PUMA covering multiple neighboring counties.

Immigration Court Filings. The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) publishes monthly county-level counts of new filings for immigration court proceedings, based on Justice Department administrative court records. These cases are typically deportation proceedings for non-citizens who have entered the U.S. without a visa or other permission. Data are reported for the immigrant’s intended county of residence. There are documented problems and errors with these data. Still, the monthly count of new cases in this database follows the trend in Custom and Border Protection encounter data, growing in the spring of 2021, spiking in late 2023, and then declining in mid-2024. Places that have been in the news for local immigration surges, like Springfield OH and Aurora CO, show higher rates of immigration court filings. Therefore, my third measure is a county’s immigration court filings from government fiscal years 2021 to 2024 (October 2020 to September 2024), divided by its 2020 population, based on county totals on the TRAC website.

We should not expect these three sources to give the same answer to how much immigration a county has had since 2020. In particular, the TRAC court-filing data covers only those who entered without a visa or other permission, while the two Census survey-based sources cover both authorized and unauthorized immigrants in theory and plausibly have better coverage of authorized immigrants. (The ACS asks about citizenship status and nativity, but not about immigration status. Estimates of the unauthorized immigration population come from sources other than the Census Bureau.)

Even the two Census-based measures use include somewhat different people: movers between the 50-states-plus-DC and Puerto Rico areconsidered international migrants in the Census population estimate measure (that is, measure #1) but not in the ACS microdata measure (measure #2). Furthermore, the population-estimates measure (measure #1) has the advantage over the ACS microdata measure (measure #2) of being available at the county level, without making any geographic adjustments, but the ACS microdata measure has the advantage over the population estimates measure of being more current and not extrapolated from lagged data.

I make no attempt to combine these three measures into a single best-guess estimate of recent immigration to each county. These three measures are too different conceptually and methodologically to combine them without making arbitrary assumptions. Instead, I describe what each of them shows, and then look at each separately in relation to the 2024 vote.

Recent immigrants live where earlier immigrants do – with important exceptions

The three local recent immigration measures show similar geographic patterns despite their conceptual and methodological differences. Across all counties, the correlation between the recent immigration rates as measured by the Census population estimates and the ACS microdata is .90 – this is so high because the Census population estimates for immigration are based on lagged ACS data. The court-filings immigration rate has a .58 correlation with the Census population estimates and .60 with the ACS microdata; as the conceptual differences suggest, the court-filing measure is the relative outlier of the three.

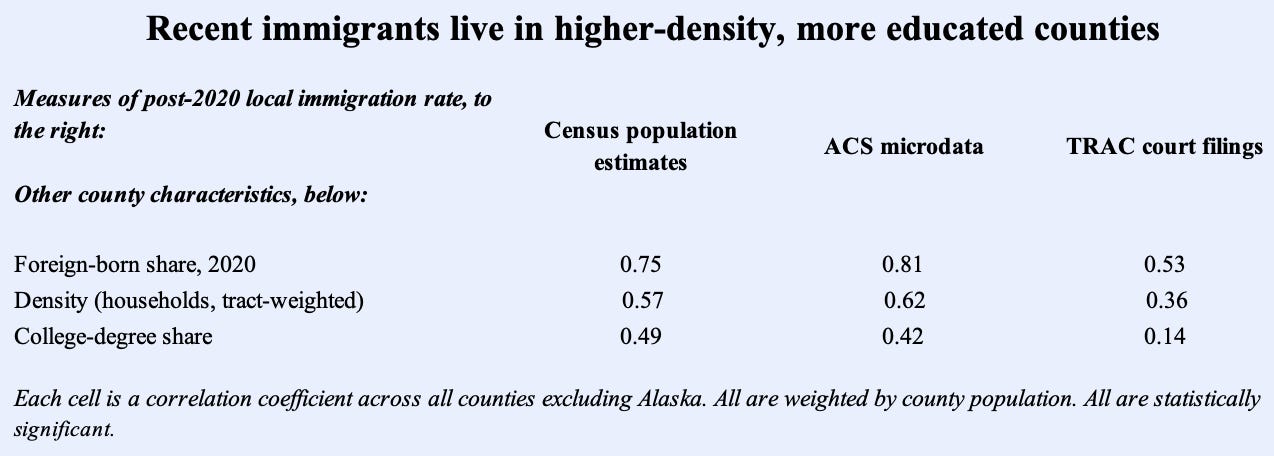

All three measures show that recent immigration has been highest in places where earlier immigrants live. The correlation between each measure and the county’s foreign-born share in 2020 is .75, .81, and .53; the court-filings measure had a lower correlation with the 2020 foreign-born share than the other recent-immigration measures did. Overall, therefore, recent immigration followed the broad geographic patterns of immigration prior to 2020.

Just as the foreign-born population in 2020 was greater in denser and higher-education counties, recent immigration has been too. All three measures of recent immigration are positively correlated with county density and educational attainment, though the relationships are weaker for the court-filings measure.

Looking at the metros with the highest rates of recent immigration on each measure gives more color. There is more overlap between the Census population estimates and the ACS microdata than with the TRAC court filings data. Both the Census estimates and ACS microdata include several college towns, where immigrants are likely to enter with visas, while the top immigrant list for court filings includes more border metros. Notably, Springfield OH makes the court-filings list; a ranking of top counties instead of metros would include Arapahoe, CO, which contains the bulk of the city of Aurora. Springfield, OH and Aurora, CO are two of the places with exaggerated or debunked claims about immigrants leading up the election.

Large metros that rank significantly higher on the court-filings measure relative to the survey-based measures include Denver, Fresno, Austin, and Salt Lake City. This is consistent with the city of Denver’s claim that it has received more migrants per capita than all other non-traditional-gateway cities.

All of this suggests that the court-filings measure is picking up something distinct from the survey-based immigration measures, and aligns with places that gained national attention about immigration.

Local recent immigration rates did not affect local vote swings

At first glance, it looks like places with lots of recent immigration swung more toward Trump in 2024. Many of the counties with the highest recent immigration rates, like Miami-Dade, the Bronx, Queens, and Hudson and Passaic counties in northern New Jersey all swung toward Trump by around 20 points. All three recent-immigration measures are strongly correlated with the swing toward Trump between 2024 and 2020. Higher-immigration counties on average were still more likely to vote for Harris over Trump in 2024, but not as much as they voted for Biden over Trump in 2020.

However, recent immigration is correlated with where the foreign-born population was in 2020, which tended to be concentrated in higher-density and higher-education counties. And with most immigrants in recent years and decades coming from Latin America or Asia, all of these foreign-born and immigration measures are correlated with the racial and ethnic makeup of a county. Race and ethnicity, education, and density all were themselves correlated with changes in the 2024 vote compared with 2020. To determine whether recent immigrant surges swung the vote in particular counties, it’s important to control for all those other correlated variables – including the 2020 foreign-born population in order to focus on the recent immigrant surge since then.

Taking into account demographic and economic factors that affected the vote swing – like race and ethnicity, education, foreign-born share in 2020, and more – recent immigration rates had no effect on how a county’s vote swung in 2024 relative to 2020. There was no swing toward Trump, on average, in counties that experienced bigger immigration surges since 2020 – regardless of which of the three measures of recent immigration you look at.

Even though immigration was among voters’ top concerns and was divisive along partisan lines, any effect of immigration on the election outcome was a reaction to national conditions, not to local immigration rates or localized effects. This is a similar finding to the role of economic conditions: local economic performance during the Biden Administration had little impact on the county vote swing, even though the economy was voters’ top concern.

Despite the old adage that all politics are local, the politics that mattered in the 2024 presidential election were national, not local.

Special thanks to Julia Gelatt for generously helping me understand and explain the immigration court-filing data.

County vote data are from Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections v0.3, updated 11/12/24. All correlations and regressions are weighted by county population or county total votes cast.