How could health insurance change with the 2024 election?

Changes in Affordable Care Act subsidies could impact coverage rates, the health insurance market, and overall health

Pandemic relief in the American Rescue Plan (ARP) passed in March 2021 included more generous financial assistance towards health insurance purchased on insurance marketplaces in 2021 and 2022, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) extended these enhanced subsidies through 2025. A key policy question as we head into the 2024 election is whether those enhanced subsidies will be extended through additional legislation prior to the 2026 enrollment season. We explore the ways the expiration of the enhanced subsidies could impact the health insurance market, health insurance coverage and overall health.

How did the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act change health insurance subsidies?

Before 2021, individuals and families with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL) were not eligible for premium tax credits through the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In 2021, the ARP changed this by capping the amount that individuals and families need to pay towards a benchmark plan at 8.5 percent of their household income. The subsidies were also more generous at lower levels of income: for families with incomes less than 150% of FPL, the benchmark plan was fully subsidized, rather than requiring these families to pay between 2 and 4 percent of their income towards health insurance.

While the enhanced subsidies granted in the ARP were aimed at providing immediate relief during the pandemic and only applied to 2021 and 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 extended them through 2025.

What role have subsidies and other federal actions had in health insurance coverage since 2010?

A series of policy changes over the last decade have shaped health insurance coverage and the market for health insurance. While Americans over the age of 65 are almost universally covered by Medicare, those below the age of 65 must obtain health insurance from one of many sources, often a current employer. In 2009, almost 18 percent of non-elderly Americans were uninsured, and while some may have been uninsured by choice and others received financial assistance towards health care from other sources, increasing affordable access to insurance coverage became a key policy issue in the Obama Administration, and eventually led to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in March 2010.

The ACA marked the most significant shift in the U.S. health insurance landscape since the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. The law expanded Medicaid, established health insurance marketplaces, provided subsidies for low and middle-income Americans to purchase insurance, and introduced a package of reforms to the insurance market. It also imposed a tax penalty on those without health insurance coverage, known as the individual mandate.

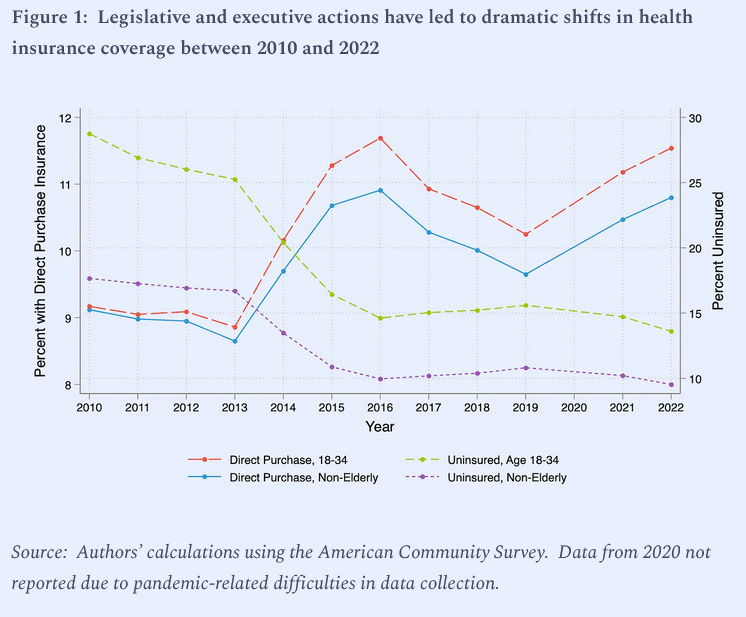

As shown in Figure 1, these changes collectively had a large impact on insurance coverage. By 2016, two years after the ACA’s main provisions took effect in 2014, under 10 percent of non-elderly Americans were without health insurance. Figure 1 also shows that the drops in uninsurance were accompanied by sharp increases in the share of the non-elderly population purchasing insurance directly from insurance companies, including subsidized coverage purchased on the health insurance marketplaces that were set up as a result of the ACA. Studies have confirmed that the subsidies, delivered through premium tax credits, were responsible for approximately 40 percent of the increase in health insurance coverage, and that Medicaid expansions accounted for the remaining 60 percent.

After the election of Donald Trump in 2016, there were several attempts to weaken or repeal the ACA. While efforts to repeal the ACA ultimately failed, executive actions, such as reducing the open enrollment period, and legislative actions, such as the elimination of the individual mandate in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, contributed to higher rates of uninsurance over this period, peaking at 10.8 percent in 2019.

In 2020, the Secretary of Health and Human Services declared a public health emergency due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act passed in March 2020, states that kept Medicaid beneficiaries continuously enrolled through the public health emergency, regardless of a change in eligibility, were eligible to receive additional federal funds. These changes resulted in higher enrollment in Medicaid and helped many Americans keep access to health insurance despite the unprecedented job losses in the spring of 2020.

The Biden Administration carried on these policies, and in addition, reduced the cost of premiums and expanded eligibility for financial assistance to purchase coverage through insurance marketplaces beginning in 2021 as described above. These enhanced subsidies reversed the downward trend in direct purchase insurance rates (see Figure 1) and contributed to record low levels of uninsurance among non-elderly Americans in 2022 (9.5 percent). On April 1, 2023, the Medicaid continuous enrollment condition ended, allowing states to terminate coverage among those who are no longer eligible.

What are the potential consequences of letting the enhanced subsidies expire?

CBO estimated that these enhanced subsidies would result in additional federal budget outlays of approximately $20 billion per year. What other outcomes were achieved as a result of this spending, and how would pulling back on this spending change insurance coverage and the market for health insurance? We turn to a large body of evidence that has amassed since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, and explore the possible implications of these more generous subsidies expiring after 2025.

Insurance coverage:

In 2021, the Urban Institute’s Health Insurance Policy Simulation Model (HIPSM) projected that the number of people uninsured would drop by 4.2 million, or almost 14 percent, in 2022 if the ARPA’s enhanced marketplace subsidies were permanent, suggesting that the expiration in 2025 could impact uninsurance rates dramatically. As discussed previously, recent data have shown upticks in insurance coverage, coupled with increases in direct purchase insurance, that occurred in tandem with higher subsidy rates. While these statistics do not tell us about what coverage would have looked like without higher subsidy rates, prior work has shown evidence that the ACA subsidies resulted in higher insurance coverage than would have occurred otherwise. Other studies have shown that the benefits of health insurance for the previously uninsured include improvements in health, reductions in out-of-pocket spending, reduced medical debt and reduced mortality. Overall, the loss in health insurance coverage that could happen if the subsidies expire is likely to be accompanied by reductions in the health and economic characteristics of those who lose coverage.

Risk composition:

The enhanced subsidies improved overall risk composition by encouraging young, healthy individuals to enter the market. These individuals are more price-sensitive, and are more likely to enter the market as subsidies increase. As a result, subsidizing this group can lower premiums and avoid the selection problems that can cause insurance markets to unravel. One example is young men – since 2010, the share of men 18-45 without health insurance has halved, from 33.2 percent in 2010 to 15.9 percent in 2022.

Competition:

An analysis from the Urban Institute showed that the number of insurers entering the market has steadily increased since 2018 and that large commercial insurers like Aetna, Cigna, and UnitedHealthcare have re-entered with more competitive premiums. Growing demand is a primary driver of entry; CMS reported that marketplace enrollment climbed to a record of 21.3 million during the last enrollment period. Additionally, improvements in risk composition have also made it more attractive for insurers to enter.

The increased participation of insurers is associated with lower premiums and greater consumer choice. A 2023 analysis of insurer participation on ACA marketplaces found that in areas where there is a single insurer in the market, premiums were higher by $128 relative to a market with five or more insurers. Thus, allowing the enhanced subsidies to expire increases the risk of insurer exit, as more low-cost plan participants would exit the pool and hurt margins. Regulatory uncertainty can also lower insurer participation and competition, as was the case in 2018.

Spillovers:

Since health insurance increases the demand for health care services among the previously uninsured, it is possible that higher rates of health insurance could negatively impact those who were already insured by reducing access.

However, one study that investigated whether Medicare beneficiaries had different outcomes across states that did and did not expand Medicaid found no evidence that either utilization or spending for primary care services changed differentially. Similarly, another study found that while the ACA changed the composition of payers, there was no significant change in the quality of care experienced by those already insured. These studies do not rule out the possibility that the additional coverage induced by enhanced subsidies leads to negative spillovers, and prior work that examined the effects of Medicaid expansions before the ACA suggests that negative spillovers are most likely to occur among those dually enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid who are both low-income and aged or disabled.

Incidence:

A key consideration when evaluating subsidies is incidence, whether a subsidy lowers premiums for consumers or passes through to the insurance companies.

The ACA subsidies use price-linking to promote greater affordability, meaning that subsidies are proportional to premiums. However, this shields consumers from the direct impact of price hikes, potentially encouraging insurers to raise premiums. Using a model estimated with Massachusetts insurance exchange data, Jaffe and Shepard (2020) found that price-linking increases prices by 1–6 percent, and much more in less competitive markets. Similarly, Decarolis, Polyakova, and Ryan (2018) found that vouchers perform much better than proportional subsidies and minimize the amount of transfers from taxpayers to firms. Fixed subsidies retain the elasticity of demand and preserve the link between prices and marginal costs.

In light of these findings, it is important to couple subsidy extensions with measures to restrain market power and uphold the connection between prices and marginal costs. Especially in areas with low insurer participation, it may be expedient to move toward a fixed, rather than price-linked, subsidy.

Conclusion

The ongoing debate about the future of health insurance in the United States is set to be a key issue over the next few years, and will be influenced by the results of the 2024 election. The temporary enhancements to health insurance subsidies under the American Rescue Plan (ARP) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) have lowered uninsured rates to record levels and reversed the decline in direct purchase insurance rates that occurred due to executive actions undertaken during the Trump administration.

Greater affordability brought more families above 400% of the FPL and young adults into the marketplaces, bolstering demand and risk competition in the marketplace. This led more insurers to enter the market, increasing competition and the number of plan offerings to consumers. Higher competition, in turn, can ensure that higher subsidies pass through to consumers in the form of reduced premiums. Competitive markets for health insurance could also reduce the government costs for subsidies by reducing the cost of the benchmark plans that the subsidies are based upon.

A fundamental question is whether subsidy extension merits the cost. The CBO estimated the permanent extension of subsidies would increase the deficit $247.9 billion over 10 years, a substantial cost. However, this figure represents only the budget outlays and does not account for the other benefits of lower rates of uninsurance described above.