How can we strengthen the direct care workforce?

Policymakers have a wide range of policy levers available to address direct care worker shortages.

The direct care workforce provides essential care to people who need help with activities of daily living, but the care workforce is relatively low-paid and struggles to keep up with the growing demand for their services. Some institutional features help explain why market forces could struggle to address worker shortages and highlight potential solutions to the mismatch between the supply of direct care workers and demand for care services.

Who are direct care workers and how has this workforce been evolving?

Direct care workers is a term that encompasses an estimated 3.2 million nursing assistants, personal care aides, and home health aides that serve to assist older adults and people with disabilities, as classified by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Direct care workers are employed in a variety of different settings, including skilled nursing facilities, hospitals, community-based residential care settings, and private homes.

Direct care workers assist their clients with daily tasks, such as dressing, bathing, and eating, and may also include meal preparation, housekeeping tasks, errands, appointments, employment and/or social engagement, and some clinical tasks, such as wound care or blood pressure readings, under the supervision of a licensed professional.

Compared to the workforce as a whole, the direct care workforce has a much larger share of women (85 percent, compared to 47 percent overall) and a smaller share white (57 percent, compared to 77 percent overall). These occupations are among the lowest-paid occupations, with median wages of approximately $15.52 per hour, resulting in high rates of poverty and public assistance use among this workforce. Turnover in this workforce is high, with one study estimating that 94 percent of nursing staff hours in nursing homes turned over annually in 2017-18.

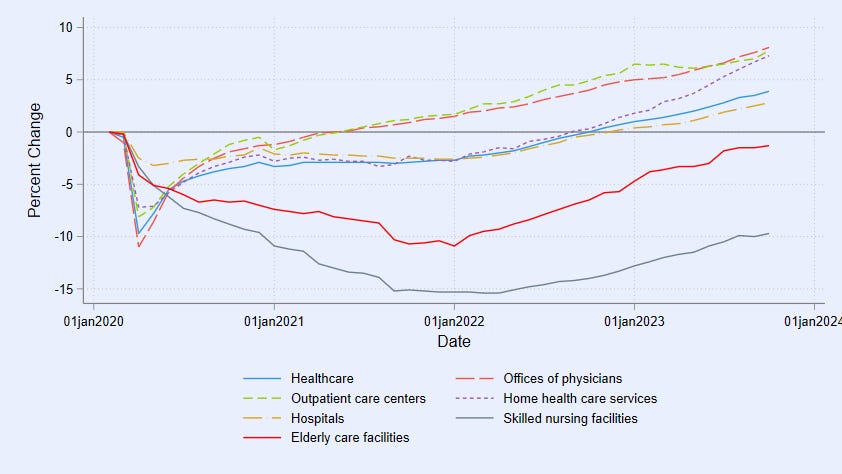

While employment has rebounded in many subsectors of health care, it is still lower than February 2020 levels in elderly care facilities and skilled nursing facilities. As shown in the figure, employment in these areas continued to decline until January 2022, and has seen a slower increase than other areas.

Employment levels reflect both supply and demand, and levels of employment do not necessarily indicate whether there are workforce shortages. In particular, the total number of residents per day across all nursing home providers is 9 percent lower in November 2023 compared to February 2020 according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Employment in those facilities is down proportionally; the relative importance of changes in resident demand and worker labor supply is not clear.

Economists usually think about shortages as short-term phenomena - if demand for a particular profession is higher than supply, employers should lift job quality offers through higher wages (or non-wage amenities) to draw more people into the profession. However, data on job openings shows that health and social assistance job openings have grown faster than job openings economy-wide since February 2020, while wages have not increased significantly more in this sector.

Employment in the health sector has largely rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, but elderly care facilities and skilled nursing facilities still lags behind

What could lead to a sustained mismatch between supply and demand in the direct care workforce?

Some features of the labor market for direct care workers may have implications for the ability of market forces to address supply and demand mismatches. The hospital industry stands out for having among the least employer competition and highest degree of employer concentration in the private sector and the clearest evidence that employer mergers cause wage decreases. Registered nurse and health support jobs requiring preparation are two of the largest occupational groups employed by local oligopsonists (employers whose competitors make up only a small share of total employment). Research has shown that firms with market power may maximize profits by underpaying and underemploying certain occupations. Employers with market power will tend to post job openings with wages and benefits that are too low to attract applicants; they earn higher profits by keeping incumbent workers’ wages low and accepting high vacancies and turnover. Incumbent workers will want raises if new hires come in with higher wages and that erodes profit though it fills vacancies and reduces turnover. Some studies show that increases in labor market concentration (for example, driven by hospital mergers) lead to lower wage growth among nurses, pharmacists, and other health care workers requiring intensive formal training, while other studies have findings more consistent with perfect competition.

Another factor that could prevent entry in certain occupations is occupational licensing requirements. Licensing and training requirements of certified nursing assistants and home health aides have the goal of raising quality for care recipients above some minimum level. However, sometimes occupational licensing can impose barriers to labor supply, raise the price of goods and services, and make it more difficult for workers to take their skills across state lines. These tradeoffs need to be well-understood in order to determine the efficient level of licensing requirements for direct care jobs. States can assess costs and benefits of weakening licensing requirements and expanding scope of practice to include workers with less stringent qualifications.

A significant share of long-term care services and supports are paid for by Medicaid, which sets reimbursement rates for nursing homes and home and community-based services administratively. While setting these rates high could substantially increase public expenditures, setting rates too low could limit the ability of firms to fill their needs by appropriate levels of staffing. In general, Medicaid reimbursement rates are lower than rates paid by Medicare or private payers, and low Medicaid reimbursement rates are thought to be a factor in poor quality and low staffing levels in nursing homes.

Some recent forces could compound any one of these issues. The rise of flexible work alternatives in other sectors of the economy combined with a heavily female labor force could reduce the number of direct care workers if some of these workers value more flexibility than direct care jobs can generally provide, and rising wages in occupations that may compete for these workers could also reduce the pool of potential direct care workers. In addition, direct care occupations are extremely labor-intensive and cannot easily be substituted by technology. Finally, an accelerated rise in the share of the population that’s elderly over the next few decades will accelerate demand for care services, and if market forces don’t result in more direct care workers, the mismatch is likely to grow.

Policy solutions should focus on enhancing job quality and increasing the pool of potential direct care workers

Improve job quality and patient care via increased reimbursement rates

To increase employers’ ability to improve job quality and to make the sector more attractive to potential workers, increasing reimbursement rates from Medicaid and Medicare is a possible path. This would raise public outlays but may have benefits in terms of quality of care and job quality.

An argument against this policy is that higher reimbursement rates might serve to increase provider profits rather than passing through to improved care and job quality. Indeed, evidence shows that private equity investors have actively acquired long-term care providers and found creative ways to pull resources toward profit and away from care and job quality.

To assure that extra resources substantially go towards improving care quality and job quality, rather than just increasing provider profits, policymakers could consider coupling reimbursement rate increases with mechanisms that achieve these goals, such as minimum staffing requirements or higher minimum wage and benefit standards for direct care workers. Some states have adopted wage pass-through laws that automatically raise reimbursements to the extent that they reflect care worker compensation increases, and evidence shows these have increased pay, staffing, and, to some extent, care quality. Minnesota recently created the nation’s first nursing home labor standards board that brings together public officials, management representatives, and labor representatives to set compensation and health and safety standards for the sector. This will include a minimum wage above the general state minimum. Policies to increase staff:patient ratios (such as those recently proposed by CMS) improve job quality and retention but increase the quantity of labor needed to serve a given set of patients. Evidence shows that following minimum wage increases, both nursing home job quality and resident care quality increased, and that nurses in areas with higher minimum nurse staffing ratios experienced higher real wage growth.

Health care employers can improve job quality, which literature has shown will help attract new workers to the sector and help retain and increase the productivity of the incumbent workforce while reducing their need to attract new workers to the sector. To some extent, employers can earn equal profits via either a low job-quality, high-turnover personnel strategy that puts more resources towards recruiting, onboarding, and training or a high job-quality, low-turnover personnel strategy that saves on those costs by investing in higher compensation and better job amenities. The latter can generate productivity and care quality benefits that come from longer job tenure and require a smaller number of total workers passing through the sector. Moving towards the “high job quality” strategy can require changes in organizational design such as staffing, scheduling, and design of career ladders, as well as compensation. Minimum labor standard policies can shift the health care labor market towards higher job quality.

Increasing the supply of trained direct care workers

To directly increase labor supply to the sector, federal immigration reform is a leading candidate. Many countries around the world produce adults already trained and experienced as health care workers, and federal immigration laws create barriers to productive immigration of these (and other) workers. Evidence shows that increased immigration improves nursing home staffing and outcomes for patients. For the U.S., gaining the skills and time of these adult workers without having paid any of the expense of training them is a huge economic free lunch. However, to the extent that there are not enough trained direct care workers worldwide, this type of policy intervention only shifts the problem rather than solving it.

Industry often advocates for public investments in occupational training programs, to increase the supply and reduce their cost of ready workers. Employers tend to prefer that the public sector, rather than the employer, pay for workforce training investments because their costs are lower and they worry employees might leave after getting employer-paid training. Many impressive sectoral training programs that enhance trainees’ employment opportunities at multiple local healthcare employers do have a strong public investment rationale. In labor markets that are competitive such that each employer is reluctant to invest and where potential employees are credit constrained, public investment in sectoral training or registered multi-employer apprenticeship programs can make sense. In contrast, where health care employers face less competition for talent and have more market power, they are willing to invest more in training because the employer expects trainees will have nowhere else to work. The case for public investment may be weaker in these cases, as the employer already stands to reap the benefits of increased worker productivity.

Including labor and community institutions in governance in addition to management can help ensure that job quality improves alongside labor supply. Multi-employer investments in registered apprenticeship programs with pathways from career and technical education in high schools and community colleges can also help workers and employers learn more about each other, find strong fits between workers and careers, and help finance training investments.

State and local occupational licensing reform also offers some limited promise. Occupational licensing reform is more of an issue for health care workers in more technical roles and less for direct care staffing, where certification and licensing requirements tend to be considerably less stringent already. However, easing unproductive requirements and encouraging greater harmonization and reciprocity across local and state licensing authorities may offer some help.

Provide direct care workers more choices and opportunities

Policies that respect and protect care workers’ right to organize and collectively bargain in the face of management opposition can also improve job quality and make the sector more attractive for potential workers. Evidence shows that health care worker unionization tends to increase labor productivity. The federal PRO Act offers a broad range of reforms to strengthen labor rights. Some states have also created laws that recognize home care workers’ rights to organize and collectively bargain, which seems to have helped pull more resources to the sector, increased job quality, and should attract workers to the sector. Labor management partnerships in unionized health care organizations can sometimes unlock substantial productivity advances.

For decades until very recently, antitrust regulators paid attention only to the consumer market implications of proposed health care company mergers. More vigorous attention to mergers’ labor market implications could help promote job quality by increasing competition in local health care labor markets and preventing increases in employer market power. The Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division’s 2023 proposed merger guidelines advocate for attention to local labor market implications. Some states have given their attorneys general greater authority to review mergers.

Freeing workers to take jobs with competing employers and equipping them to make better decisions about where to work can also increase job quality and competition in health care labor markets. Broad non-compete and non-disclosure clauses have stifled competition. One in four workers in a healthcare support occupation, one in five in a personal care service occupation, and one in five in the health care and social assistance industries report being bound by noncompete restrictions. Many states have taken action to free workers from noncompete restrictions and the Federal Trade Commission has proposed a broad national ban. Where this has already occurred, wages have tended to rise. Narrowing the enforceability of nondisparagement and nondisclosure clauses can promote the flow of reliable information to job seekers about the quality of prospective jobs, improving competition.

Conclusion

The direct care workforce provides essential care to those who cannot perform certain daily tasks without assistance, and the demand for their services is likely to grow as the population ages. Several factors prevent market forces from solving worker shortages in this area. However, policy solutions to mitigate these barriers can improve job quality and compensation for these workers and result in improved outcomes for care recipients.