Growing Costs of Natural Disasters are Stressing Property Insurance Markets

Fixes require addressing underlying drivers of losses and offer an opportunity to improve a complex and flawed system

Widespread availability of property insurance is a key part of the U.S. financial system: it both supports mortgage access and enables financial resiliency by providing an influx of funds for post-disaster recovery. But concentrated losses from large extreme weather events pose an existential risk for insurers and are expensive to underwrite. Insured losses from natural disasters in the U.S. have been rising steeply from a combination of climate change and the rapid growth of people and property in risky areas: 2023 saw U.S. home insurers take $15.2 billion in net losses, the worst performance since at least 2000. In response, insurers are raising premiums and withdrawing coverage and property insurance markets are looking increasingly shaky in states across the U.S. A sudden withdrawal of insurers from underwriting windstorm, hail and wildfire risks - similar to the withdrawal from flood insurance that occurred in the early 20th century - is certainly possible.

Losses from disasters loom large for households and local communities but, at approximately $100 billion per year, are more than manageable at the national level. Sensible policies to address faltering insurance markets will encourage long-term and forward-looking risk reduction measures and avoid broad, untargeted premium subsidies that mute risk signals and raise costs over the longer-term. A Federal program to provide at-cost reinsurance coverage for catastrophic losses, while simultaneously requiring reforms to expand coverage, reduce risks and stabilize markets, would address a key driver of insurer withdrawals while also improving on the existing overly-complex disaster insurance system that leaves many underinsured.

What is going on in property insurance markets?

A host of recent reporting has highlighted growing instabilities in property insurance markets across the U.S. Nationwide, premiums increased 13% in real terms between 2020 and 2023, with much faster growth in some areas. These stresses appear to be spreading beyond the hurricane-exposed Gulf Coast, affecting a wide range of states exposed to wildfires and windstorms, from New York to Iowa to Colorado and California. Despite rising premiums, there is also anecdotal evidence of declining quality of coverage. Insurers appear to be increasingly adding sublimits, exclusions, or additional deductibles to policies that limit their losses in the event of a large disaster. In some areas, insurers have been slow to pay out post-disaster claims or have cut assessed damages.

Even more disruptive for property-owners than growing premiums and declining quality of coverage is the complete lack of availability of private insurance at any cost, as insurers exit or limit underwriting in certain areas. Unavailability of insurance causes immediate distress for property owners, who are typically bound to long-term mortgages that require coverage. States affected by insurance withdrawals have typically established “last-resort” public plans for properties unable to find a policy in the private market. The rapid growth in these plans, which are ultimately backed by all policy-holders or taxpayers in a state, is a clear signal of growing unavailability of private insurance: total underwriting by public plans reached a new record high in 2023 at just over $1.3 trillion in exposure; Florida, California and Louisiana all saw their plans more than quadruple in the five years from 2018 to 2023 (Figure 1).

Exposure of public plans dipped over the 2010s, largely due to a concerted effort in Florida to move policies off the state-run plan Florida Citizens. Despite major reform efforts, highest premiums in the country, and additional state intervention in the form of a public reinsurance plan (backed by state borrowing capacity and taxing authority), Florida has been unable to stabilize its insurance market. Rather it serves as a warning of where other states may be headed. Its market is dominated by small firms with highly concentrated exposure heavily reliant on reinsurance markets. Nine Florida insurers declared bankruptcy between 2021 and 2023 and the state has had to repeatedly levy emergency assessments on all state residents to cover claims from bankrupt firms. As of 2018, over 50% of underwriting in Florida was from firms unable to obtain a rating from the major credit rating agencies. Moreover, since 2018, properties have flooded back onto Florida Citizens, which is once again the largest insurer and approaching its 2011 peak size.

Why Is This Happening?

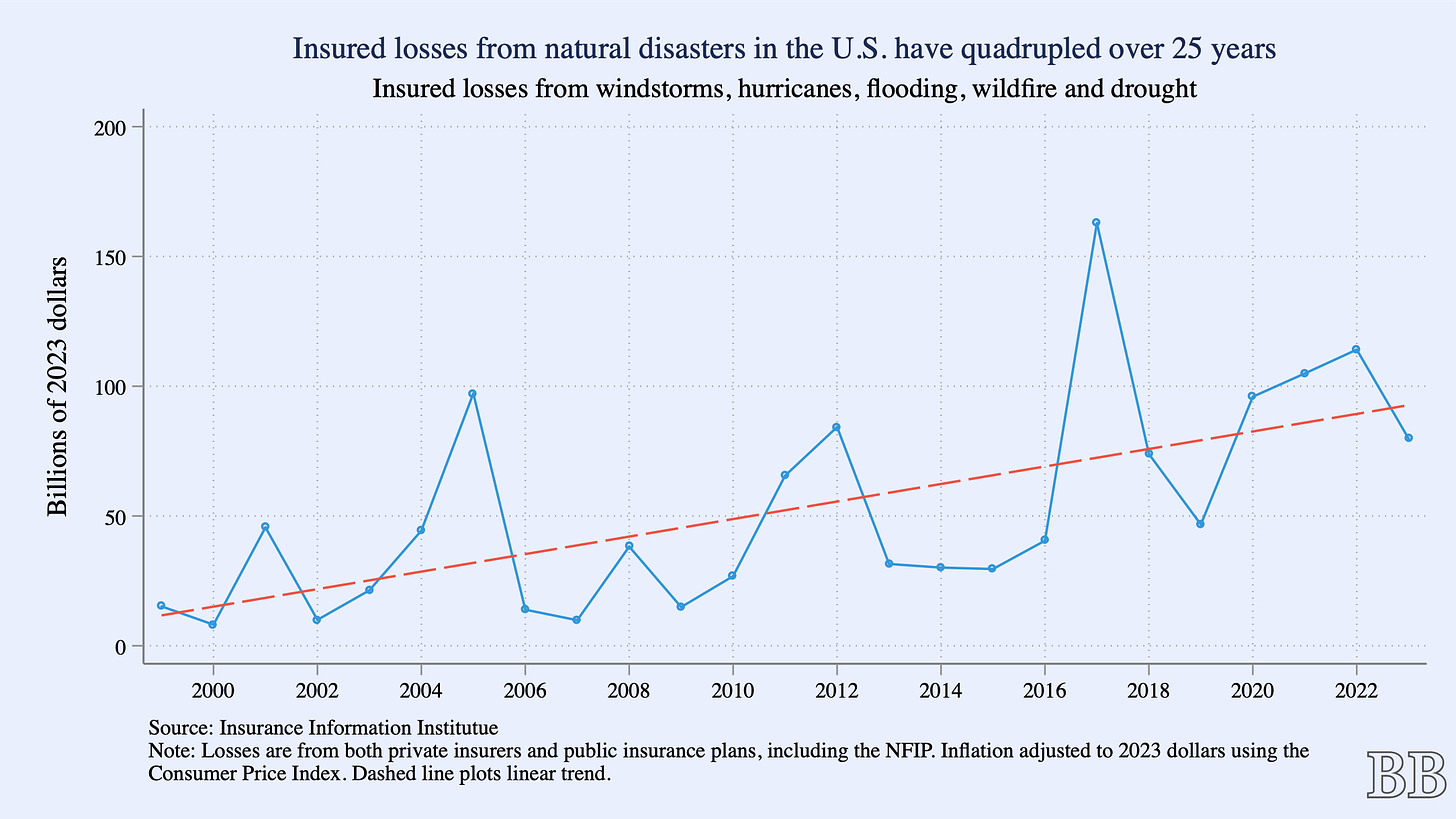

While each state has particular economic and institutional idiosyncrasies, growing losses from natural disasters is clearly the first-order driver behind rising premiums and declining availability (Figure 2).1 The frequency of extreme weather events with $1 billion or more in damages (in inflation adjusted terms) has grown steeply, from 3.3 per year in the 1980s to over 20 per year in the last 5 years. While only a fraction of these losses are privately insured, several lines of evidence – including public statements from industry executives and regulators, spiking reinsurance costs, and the concentration of largest rate increases in places at highest risk of disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires – point to growing disaster costs as a root cause of current market turmoil.

The correlated losses that come from natural disasters pose an existential problem for insurers. For most typical insurance lines, individual risks are idiosyncratic meaning aggregate claims across a large population of policy-holders are stable from year to year, and premiums can be set close to expected losses. In contrast, insured losses from natural hazards exhibit large variability from year to year, even when aggregated across all perils at the global level. Insurers underwriting these risks must maintain access to large amounts of capital to pay claims or risk bankruptcy. Insurers can transfer catastrophic risks to other entities, either through reinsurance contracts or insurance-linked securities that transfer risks to investors in public markets. But this risk transfer comes at a price that raises the cost of supplying insurance above, potentially substantially above, expected losses.

What, then, is driving the rising costs of natural disasters in the US? There are two obvious culprits: growth in the population density and capital stock in risky areas, and the effects of climate change. The number of housing units in the US has increased 30% since 2000. Much of this development has been in eastern coastal states such as Florida, Texas or North Carolina, exposed to coastal windstorms and hurricanes, or in outer suburbs in western states that impinge on wildlands vulnerable to wildfire. Because of the patchwork of locally-governed building codes across the country, only a small fraction of these will have been built to highest disaster resiliency standards.

In addition to growing exposure of people and property, climate change is also playing a role in altering the frequency and severity of natural hazards. The climate-change influence is clearest in the massive wildfires that have racked western states, Texas and Canada in recent years. Hotter weather and intense drought dries out vegetation, producing conditions necessary for rapidly-spreading wildfires. Climate change effects on windstorms, most importantly hurricanes, are more complex: there are reasons to believe climate change could reduce the number of storms but that hotter oceans will super-charge the storms that do occur, meaning a larger fraction will arrive as the most damaging Category 4 and 5 storms. (Climate change is also increasing flood-related losses due to higher sea-levels and more intense rainstorms, but the private sector plays almost no role in insuring flooding in the US; over 95% of flood policies in the US are through the Federal NFIP).

Beyond particular trends in extremes that may or may not be attributable to human-induced climate change, simply the possibility of changing extremes due to climate change could act as a destabilizing force on insurance markets. One characteristic of catastrophic risk is that expected losses are heavily influenced by rare but very large events. As one example, the 2017 and 2018 wildfire seasons in California produced losses more than twice as large as all the profits from property insurance in the state for the prior 26 year period combined. This tail risk dependency means the assessed probability of very rare but very large events has a major influence on how insurers and reinsurers understand the distribution of losses. But probabilities of these extremes are highly uncertain and the presence of climate change only increases that uncertainty. Ambiguity over extreme event probabilities introduced by the mere possibility of human-induced climate change (irrespective of any actual observed changes in losses) could act to raise insurance and reinsurance costs, increase insolvency risk and prompt insurer withdrawals from hazardous areas.2

What Should We Do About It?

So much for the diagnosis, but what, if anything, should be done? In considering policy responses, it is helpful to establish some general facts about property insurance markets and role they play in our financial and disaster-recovery systems:

Insurance against natural disasters is important. Claims payments following natural disasters are important for households to recover financially from disasters. Federal disaster aid does not make private property owners whole after a disaster. Instead, uninsured private losses from disasters are almost entirely uncompensated. Payouts from insurance claims are therefore critical in protecting households against a downward spiral into loan delinquency and bankruptcy, and may play a role in enabling broader regional recovery after a disaster.

Insurance also plays a role in enabling property ownership for low- and middle-income households through its connection to mortgage lending. Insurance secures the property that acts as collateral for the loan. Banks respond to limited disaster insurance availability by requiring higher down-payments and limiting lending. A broad withdrawal of insurance availability in response to changing disaster risks will exacerbate existing housing supply challenges and further limit opportunities for property ownership by middle-class households.Private markets for insurance against natural disasters are fragile. The continued existence of robust private markets for natural hazards should not be taken for granted. The most common and costly natural disaster in the U.S. – flooding – is essentially entirely insured by the Federal government, precisely because private insurers ceased offering coverage entirely after major flooding in the early 20th century. The correlated losses and substantial ambiguity around natural hazard losses makes them very challenging for insurers to cover. Combined with growing exposure from both climate change and unchecked development, the possibility of sudden and rapid insurer withdrawal from the natural hazard risks they still cover is substantial.

Insurance premiums provide important risk price signals. Consumers respond to prices and insurance premiums provide essential information to households regarding the natural hazard risks they face. Evidence shows that households do respond to higher insurance costs, through relocation, additional insurance coverage, and by making investments in property resilience. Direct, broad-based subsidies to insurance premiums are almost certain to backfire by muting these price signals, leading to more people and property in risky areas and raising disaster costs over the long-run.

Cost of risk transfer can push the costs of supplying insurance above expected losses. Actuarially fair insurance generally means – to economists – that consumers pay premiums close to expected loss. But if insurers need to pay to transfer catastrophic risks, then the cost of supplying insurance could substantially exceed expected loss. In recent NFIP rate reforms, for example, premiums include the program’s private-sector reinsurance costs and a 20% surcharge to finance a Congressionally-mandated catastrophic loss fund, which are added on to a property’s expected loss. Recent premium hikes in Florida and Louisiana were almost certainly linked to rising reinsurance costs. This wedge between expected losses and the costs of supplying coverage could lead to market unraveling as consumers are forced by lenders to pay for financial products at costs substantially above expected losses or, if not required to purchase it, forgo coverage entirely.

Insurance markets alone will not produce effective or efficient climate change adaptation. Insurance is almost universally an annual contract, with premium prices revised every year to reflect current risks. But properties are long-lived assets which, because of climate change, could see substantial changes in risks over their 100+ year lifetime. Efficient adaptation to climate change requires forward-looking decisions around where and how to build, where to live, and how much to pay for a property to integrate information on future climate risks. This information is not integrated in annual insurance premiums. Widespread dissemination of high-quality information on current and future climate risks and use of land-use zoning and building codes to gradually reduce exposure of the nation’s building stock to weather extremes are essential to lower climate change costs.

Disaster losses are manageable at a national level. Total losses from natural disasters in the US averaged $110 billion per year for the last 10 years, with insured losses making up just over half of that total. Although losses can loom large at the local or state level, this is a tiny fraction of an economy of over $27 trillion. Even with the growing threat of climate change, the U.S. has the financial ability to manage losses, particularly with an ambitious program of risk-reduction through zoning and building-code measures.

The Federal government holds a large fraction of disaster risk. The Federal government underwrites essentially all insured flood risk in the country. While not playing a formal role in underwriting wildfire, windstorm or hail losses, Federal backing of the mortgage market means that the Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) would likely take losses from disaster-driven mortgage default. There is some evidence that higher disaster risks prompt banks to securitize loans, transferring the risk to the Federal government. Insurance protects the government’s interest in these properties, which is why it is required for securitization. But deteriorating private insurance markets, notably in Florida, have led to pressure on the GSEs to lower their insurance requirements, a move that would increase the Federal government’s exposure to disaster losses. In addition, the Federal government is also on the hook for post-disaster reconstruction assistance, much of which goes to rebuilding damaged public infrastructure.

Our current disaster insurance system is a mess. The NFIP plays an essential role in providing flood insurance for communities around the country. But the separation of flooding from general property insurance leaves many households underinsured: only 4% of households in the country hold flood insurance and only 16% of flood damages are insured, compared to 77% of wind losses that are included in standard coverage. Many are unaware that their homeowners policy does not cover flooding, believing they are covered only to find out after a flood that they are not. Reforms to stabilize insurance markets in the face of growing risks should not double-down on these problems by further carving out specific risks from homeowners policies, but instead should be seen as an opportunity to simplify policies and expand coverage while pursuing price stability and insurance availability.

Given these stylized facts, there are three general policy approaches at the Federal level that could help address shaky insurance markets and improve the nation’s financial resiliency against extreme weather:

Take actions to reduce risks. Fundamentally, it is rising disaster-related losses that are stressing property insurance markets, so addressing the root cause of these rising losses is essential. Restricting risky development, using both zoning restrictions that steer new development away from higher-risk areas and improving building codes to require more resilient building (and require rebuilding to high resiliency standards) will begin slowing the growth in losses. Land-use and building codes are not controlled Federally, but the Federal government is directly implicated because of its role in underwriting flood risk, securing mortgages, and funding post-disaster reconstruction. Through the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard, agencies are taking important steps to attach resiliency requirements to Federal post-disaster assistance, leveraging the Federal government’s funding to achieve needed reforms.

Reducing emissions to stabilize the climate system is the other key risk-reducing measure. Inertia in the climate system means that emissions reductions will not reduce risks over the near-term. But driving global emissions to zero is essential for stabilizing global temperatures, bounding climate damages, and limiting future surprises from the climate system. To the extent uncertainty over climate-change induced shifts in the probability of extreme weather is undermining confidence of insurers and reinsurers, bounding this uncertainty through a firm and credible commitment to global net-zero emissions is important.Provide high-quality, trustworthy, useful information on current and future climate risks. The expertise on climate change and weather risks within the U.S. Federal government is unparalleled. The high-quality, public weather forecasting provided by NOAA has immense value: a recent study estimated that reduced damages enabled by improved hurricane forecasts since the 1990s paid for the costs of the program many times over. Despite the high-quality of Federal climate and weather science, research and modeling of climate risks currently occurs almost entirely in the private sector. “Catastrophe modeling” quantifies the distribution of natural-hazard related risks at the property level but is performed entirely in the private sector and can cost millions to access. Insurers often use these data for rate-setting, but models may not be accessible to regulators or the general public, creating asymmetric information and undermining confidence in the rate-setting process. Moreover, the ability of these models to account for climate change is unclear. A public capacity for climate-change informed catastrophe modeling will both help support insurance markets while also providing an essential foundation for households, local governments and businesses looking to better integrate climate risks into their decision-making. The Federal government is uniquely able to provide this essential public good.

Consider a public reinsurance program, tied to state and local risk reduction measures and insurance market reforms. The economic costs of disasters are more than manageable at a national level and widespread coverage and continued availability of insurance serves an important public interest. The current disaster insurance and risk-management system is overly complex and riddled with implicit risk-transfers to the Federal government with no requirements for risk-reduction at the state and local level. A sensible approach would be to rationalize this system by offering explicit, at-cost, transfer of catastrophic risk to the Federal government. This avoids directly subsidizing insurance premiums – property owners will still pay their expected losses – but directly tackles the catastrophic risk component that is driving insurer withdrawal and rising premiums. In return for access to the risk-transfer program, participating states must be required to enact ambitious, forward-looking risk reduction measures as well as insurance market reforms to simplify policies and expand coverage. Public reinsurance programs are common: many high-income countries exposed to disaster risk, including New Zealand, Japan, France and Spain, use public reinsurance to support insurance markets for flooding, landslide and earthquakes. The U.S. also already uses this approach, both implicitly for catastrophic flood losses via the NFIP’s ability to borrow from the Treasury, and explicitly for terrorism risks, following the collapse of the market for terrorism-related losses after the 9/11 attacks.

Conclusion

Unchecked development in risky areas across the U.S. and the growing losses and added uncertainty from climate change are acting together to undermine insurance markets. Until global emissions fall to zero, the climate is likely to keep generating surprises in the form of newly-damaging extremes: current market instabilities are unlikely to be a one-time adjustment, but instead signal the beginning of a new era of continuous surprises and risk re-pricing. Given the challenges in underwriting natural disasters, the private market alone may well not be able to continue offering widespread coverage. But collapse of disaster insurance coverage is not inevitable and would unnecessarily increase the disruption from coming climate changes and shift risks onto those less able to manage them . Disaster losses are more than manageable at the national level, particularly with an ambitious program of forward-looking risk-reduction and a firm commitment to global greenhouse gas emissions reduction.

Regulation of insurance rate increases in California has almost certainly slowed premium growth in high-risk areas, kept premiums artificially low and contributed to insurer exit from the state while Florida insurers have faced high litigation costs. Both states have taken action in recent years to address these problems.

These effects could be exacerbated by the “winner’s curse” phenomenon highlighted in a recent working paper: in competitive markets, consumers will opt for the lowest-priced coverage, but this is most likely to be under-pricing the true risk if insurers are not confident in extreme event probabilities. In the presence of ambiguity a rational response from most insurance firms will be to add an “ambiguity premium” to policies in risky areas to avoid taking underwriting losses, further driving the cost of coverage above expected losses.

Really informative, thank you.

Great piece... thanks.