Bad news bias in gasoline price coverage

TV coverage of gas prices is negatively skewed and it's only getting worse

Negative news drives consumer engagement, creating incentives for news media to emphasize bad news. This piece quantifies bad news bias in TV coverage of gasoline prices, using a dataset of over one million transcripts from six major TV outlets spanning 2004 to 2023.

TV coverage of gas prices ramps up sharply when the nominal gas price hits $3.50 per gallon and is consistently negative in tone. The ramp-up is steeper for cable outlets and steepest for Fox News. Because the $3.50 inflection point is stable in nominal terms, the real threshold at which the media ramps up their coverage of gas prices has decreased by one-third over time.

Along with their direct impact on American pocketbooks, gas prices have been shown to impact inflation expectations and consumer sentiment. To the extent that skewed media coverage influences perceptions, bad news bias in the coverage of gas prices could have meaningful economic consequences.

TV coverage ramps up sharply when the nominal gas price hits $3.50 per gallon

We analyzed 1.1 million TV transcripts covering all shows aired by ABC News, CBS News, NBC News, CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC between March 2004 and December 2023.1 These transcripts were accessed via the LexisNexis Nexis Uni database. We classified a show as covering gas prices if the transcript contained the terms “gas price(s)” or “gasoline price(s)”. For transcripts that mentioned gas prices, we classified the coverage as positive or negative in tone using a natural language processing algorithm. To measure gas prices, we used the national average gas price from AAA, both in nominal amounts and inflation-adjusted to December 2023 using the CPI-U.

High versus low gas prices have equal and opposite impacts on consumer pocketbooks, and could in principle be equally newsworthy events. In reality, the media only covers gas prices when prices are above average. Figure 1 plots the relationship between TV coverage and nominal (not inflation-adjusted) gas prices over 2004-2023. The plot also shows the lines from a regression model of the relationship between TV coverage and gas prices that allows for an inflection point at the price that best fits the data.2

The plot shows that very few TV programs mention gas prices when the nominal price is below $3.50 per gallon. Above this level, TV mentions of gas prices ramp up linearly, with each 50-cent increase in gas prices raising the coverage rate by 7.5 percentage points (p.p.). Alternatively put, while only 2.7 percent of transcriptions mention gas prices on average, 10.4 percent mention gas prices when the price hits $4.00, and 18.2 percent mention gas prices when the price hits $4.50.

While nominally stable, the real ramp-up point has decreased substantially over time

A stable ramp-up point in nominal gas prices suggests that the real (inflation-adjusted) ramp-up point has decreased over time. Figure 2 plots the relationship between TV mentions and gas prices separately by time period, using both nominal and real gas prices. As before, we plot lines from regression models that allow for an inflection point at the price that best fits the data.

The top row shows that when using nominal gas prices the inflection point is remarkably stable, varying non-systematically from $3.45 (2004-2009) to $3.65 (2010-2016) to $3.55 (2017-2023). The bottom row shows that the real inflection point has dropped by almost one-third, declining from $4.95 (2004-2009) to $4.75 (2010-2016) to $3.50 (2017-2023).

In addition to decreasing in real terms, the inflection point is also declining relative to the distribution of gas prices over these time periods. The 2004-2009 inflection point was at the 92nd percentile of gas prices during this period, the 2010-2016 inflection point was at the 76th percentile, and the 2017-2023 inflection point was at the 64th percentile of prices over this period.

Taken together, these facts imply that over the past twenty years, the threshold at which the media ramps up their coverage of gas prices has decreased substantially in real terms. A decade ago, TV coverage would not ramp up until the real price was $4.75 per gallon; today, TV coverage ramps up at $3.50.

Outlets vary in their coverage of gasoline prices, but sentiment is consistently negative

Figure 3 examines the relationship between TV coverage and nominal gas prices separately for each media outlet, pooling data over the 2004-2023 time period and plotting best-fit lines from separate underlying regressions.3

The response of TV coverage to nominal gas prices is more than four times stronger for cable news than network news. When prices are above $3.50, each 50-cent increase in nominal gas prices raises cable coverage by 19.0 p.p. versus only 4.2 p.p. for the networks. Within the cable outlets, the response is almost 50 percent stronger for Fox News than CNN or MSNBC. For example, during the second week of June 2022 (the week before gas prices reached a record high of $5.02 per gallon), 78.4 percent of Fox News programs mentioned gasoline prices, compared to 43.2 percent of CNN and 38.4 percent of MSNBC programs.

We did not detect an effect of trends in gas prices on TV coverage. Once we controlled for the level of gas prices, the change in gas prices over the prior two weeks had no impact on coverage. We also did not detect any significant changes in the relationship between coverage and nominal gas prices based on the political party of the president.

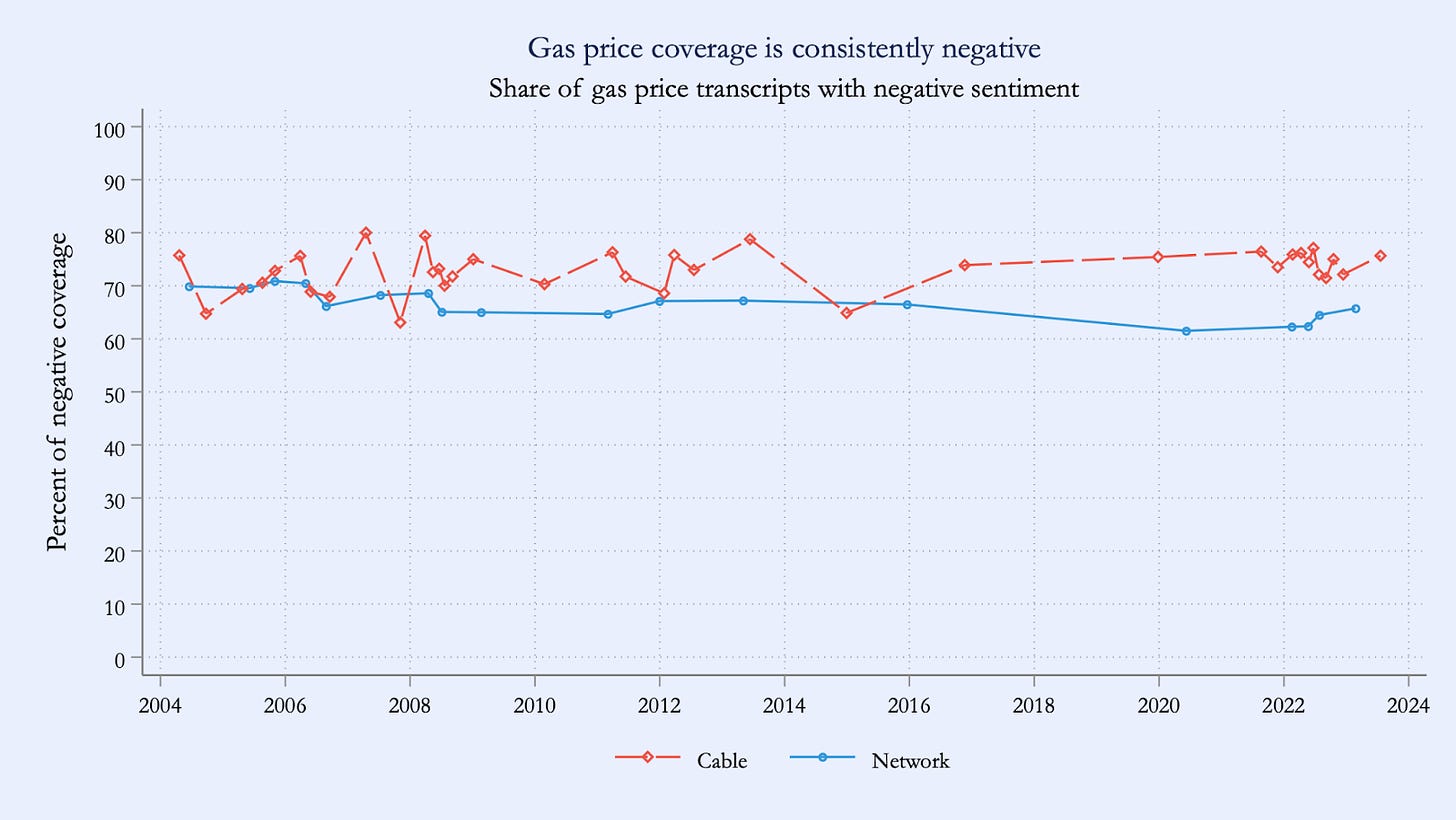

While the amount of coverage varies with the gas price, the tone of that coverage is consistently negative. Figure 4 plots the average percent of negative transcripts for cable and network outlets over time from our baseline natural language processing algorithm.4

Over time and across cable and network outlets, a consistent 70 percent of transcripts are classified as negative in tone, with slightly more negative sentiment among cable news outlets over recent years. These results are robust to using other popular natural language processing algorithms and adjusting the amount of inputted text. While we interpret these results as showing a consistent negative tone, there may be variation in tone that is not detected by our algorithms, and could be picked up as better natural language processing algorithms become available.

Skewed media coverage may bias perceptions of gas prices

A Gallup survey found that 67 percent of Americans relied on the media as their main source of information about gas prices (with 42 percent relying specifically on television news), while only 22 percent listed their local gas station as their main source of gas price information. The same survey found that consumers' interest in gas prices went beyond knowing where to find the cheapest gas, with a plurality telling Gallup they were interested in learning why gas prices were high and how high prices would impact the national economy.

Figure 5 shows the actual distribution of real gas prices and the distribution when they receive TV coverage. Specifically, to illustrate changes in coverage over time, we plot the distribution of gas prices using 2004-2009 coverage behavior (Figure 2, bottom left panel) and 2017-2023 coverage behavior (Figure 2, bottom right panel).

During our time period, real gas prices averaged $3.73 per gallon. Based on 2004-2009 TV coverage patterns, real gas prices averaged $4.17. Based on 2017-2023 TV coverage patterns, real gas prices averaged $4.55. In other words, a person who only learned about gas prices from TV would perceive them as roughly 11.8 percent higher than actual based on 2004-2009 TV coverage and 21.8 percent higher based on 2017-2023 TV coverage.

Conclusion

We analyzed over one million transcripts and found that TV coverage of gas prices exhibits a negative news bias. TV coverage sharply ramps up when the nominal gas price hits $3.50 per gallon. The ramp-up is steeper for cable than network outlets, and among cable outlets, steepest for Fox News. Because the $3.50 threshold is stable in nominal terms, the real threshold at which the media ramps up their coverage of gas prices has decreased by one-third over time.

Our findings are directionally consistent with TV outlets slanting their coverage to cater to consumers’ demand for bad news. It is unclear whether the magnitude of bad news bias we document (or the variation in bad news bias across outlets and over time) can be rationalized by consumer demand. Our analysis complements Sacerdote et al. (2020), who found that U.S. media coverage of COVID-19 was much more negative than non-U.S. coverage, and Harris and Sojourner (2024), who found that economic news has become systematically more negative in tone than what economic fundamentals would predict.

In surveys, consumers report that they rely on news media as their main source of information on gas prices. Research finds a connection between gas prices and consumer expectations about inflation and economic conditions. While we do not directly analyze the link between media coverage and consumer perceptions, it seems plausible that skewed media coverage could bias perceptions of gas prices, with knock-on effects on inflation expectations, economic sentiment, and, ultimately, real economic outcomes.

Appendix

Selecting inflection points

Let i denote media outlets, t denote time in weeks, and $X denote a candidate “inflection point” in the relationship between gas prices and media mentions. We search for the best-fit inflection point by looping over values of $X and running regressions of the form:

where

is the difference in price relative to $X, and the coefficients \beta_1 and \beta_2 are the slopes of the relationship between gas prices and mentions on either side of the inflection. The resulting R^2s, plotted in Figure A1, indicate that an inflection point of $3.50 has maximal explanatory power. The figure also shows that the models with nominal gas prices fit that data substantially better than those using real gas prices.

The table below shows the coefficient estimates from the resulting regression with robust standard errors shown in parentheses.

We also estimate models where we allow the effect on mentions to vary not only with the level of gas prices but also the change over the prior 2 weeks:

where

and

The table below shows estimates from this alternative model, with robust standard errors in parentheses as before. Neither of the \gamma coefficients is statistically distinguishable from 0 in the specification with all outlets. Across all specifications, the \gamma coefficients are generally insignificant and always small in magnitude compared to the \beta coefficients.

These networks averaged a combined primetime viewership of 23 million in 2022. Of that, roughly four million watched cable news, while 19 million watched network news. See Pew “Cable News Fact Sheet” (2023) and Pew “Network News Fact Sheet” (2023)

For a full description of the regression model, see the appendix.

For the outlet-by-outlet analysis, we focus on the relationship between TV coverage and nominal gas prices because this relationship is stable over time.

Specifically, for each transcript mentioning gas prices, we extracted the 15 sentences following the first mention of gas prices, and used a BERT-based algorithm to classify the sentiment of this text. This BERT-based classifier is a best-in-class natural language processing algorithm that has been trained to detect sentiment on the Stanford Sentiment Treebank corpora. The algorithm outputs the probability of positive or negative sentiment for each of the 27,602 excerpts mentioning gas prices. The figure shows the average probability of negative sentiment for cable and network outlets for bins of 500 transcripts. See Hashemi-Pour (2024) and Delvin et al (2018) for more on the workings of the algorithm.

Amazing work and powerful findings! Congratulations for the mention in the FT as well.

It is not surprising to me that a rise in gas prices above 3.5 (which is probably near the expected price to pay for gas at the national level over most of this period) gets attention - I bet the authors will get the same type of kink if they focus on shorter (but not too short - like 5 years+) chunks of the data and look how the kink behaves around the national 5-year average gas price.

Regardless, the lack of coverage of positive news is quite interesting. Is the Fox news kink more pronounced when a Democrat is in the office? How about MSNBC when a Republican is in the office? Would be super interesting to know.